Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

When to stick with traditional approaches and when to change them has been a basic question facing the Jewish people for quite a long time, with increased urgency in the modern era, and with what feels like breakneck speed over the past 40 years or so. The tragedy at the center of this week’s portion, Shmini, which means "the eighth", sheds some light on the issue.

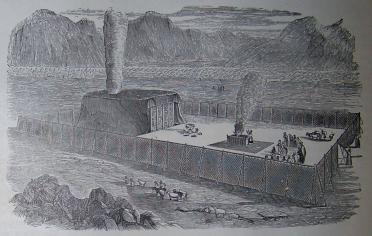

The parsha is about the eighth day of the opening of the Tabernacle, which was actually its first fully functioning day, after seven days of special inaugural rituals performed by Moshe, Aharon, and the other priests. On this 'opening day', Moshe commands Aharon and the people to bring sacrifices to the Tabernacle, "for today God will appear to you", which is, after all, the point of the Tabernacle. Aharon and his sons prepare the animal sacrifices as they are commanded, and, as hoped for "…the glory of God was shown to the entire nation. And a fire went out from before God and consumed the burnt offering and the fats which were on the altar, and the entire nation saw, and celebrated, and fell on their faces." This moment, the climax of so much work and ritual, is what the Tabernacle was all about: the palpable presence of God, experienced and witnessed by the entire people.

Unbelievably, tragically, what happens next is this:” Now Aharon's sons, Nadav and Avihu, each took his pan and placed in it fire, and placed on it incense, and brought it before the Lord; a strange fire which he had not commanded them. And a fire went out from before the Lord and consumed them and they died before God. And Moshe said to Aharon: this is what God was referring to when he said 'with those close to me I will be sanctified, and before the entire nation I will be honored', and Aharon was silent."

For centuries, commentators have debated the meaning of this story. What was the sin of Nadav and Avihu, what was the 'strange fire' which they offered, and why did they die because of it? What does Moshe mean when he says "this is what God was referring to when he said 'with those close to me I will be sanctified, and before the entire nation I will be honored'"? How could such a tragic event sanctify and honor God, and why did it happen on the joyous day of the opening of the Tabernacle?

First let’s find out what Moshe was talking about when he said to Aharon "this is what God was referring to when he said 'with those close to me I will be sanctified'"? When did God say this, and what kind of sanctification did he mean? Rashi quotes a Midrash which appears in the Talmud, which explains that, back in Exodus, along with the original commandment to build the Tabernacle, God said that the Tabernacle would be hallowed by His glory. At the time, Moshe apparently understood this to mean that it would be hallowed by the death of God's most glorious and respected servants. Moshe, in our Parsha, after the deaths of Nadav and Avihu, tells Aharon that, until now, he had thought that God meant that either he, himself, or Aharon, the two leaders of the people, would die, thereby, somehow, sanctifying and glorifying the Temple. But now that Aharon's sons have died, Moshe sees that they are in fact greater than their father Aharon or their uncle Moshe, and were therefore chosen to sanctify the Tabernacle with their deaths. This is apparently intended as a kind of consolation to Aharon, who accepts it in silence.

The notion that someone great or important would die at the inauguration of the Temple, in order to somehow sanctify it, is a strange one, and feels uncomfortably like human sacrifice (as well as a bit Christian). Apparently, it indicates that the full force and profundity of God's presence in the Tabernacle could only be communicated by the death of one or more of the leaders of the Jewish people - a dramatic indication of God's might, and of the awesome nature of His Temple and His presence in it. If this is the case, why, indeed, were Moshe and/or Aharon, clearly the greatest Jews available, not chosen to play that role? Why were Nadav and Avihu chosen, wherein lies their greatness?

To answer this question, I am going to assume that there is no secret, unknown story which explains their stature. I will assume that what the Torah tells us about Nadav and Avihu is all we need to know. If this is so, then all we know of them is the fact of their offering "a strange fire, which they had not been commanded to bring" before God. This, apparently, is their greatness, and also the act which triggered their deaths. If this is the case, and the act of offering an unbidden 'strange fire' before God places the sons of Aharon on some higher level than Moshe and Aharon, then it would seem that this spontaneous, voluntary, from-the-heart offering of incense is in some way more precious, more honorable, holier, than the commanded rites performed so obediently by Moshe and Aharon. The impetuous, unbidden, unscripted act of the sons stands in stark contrast to the days and weeks of strict obedience to the specifics of God's commandments concerning the building and operation of the Tabernacle on the part of the fathers. The values of spontaneity, imagination, and creativity, until now absent from Moshe and Aharon’s efforts to build and run the Tabernacle, are apparently greater than the values of strict obedience to the letter of the law.

And yet, for acting on these values, Nadav and Avihu are killed. This voluntary offering seems, therefore, to communicate two contradictory messages. On the one hand, when Moshe states that Nadav and Avihu are greater than he and Aharon, he underscores the value of spontaneity, creativity, and personal statement in religious activity. On the other hand, the boys’ deaths indicate that such an approach is dangerous, threatening, and, ultimately unacceptable in the Temple. The implication seems to be that there is value in their actions, but not when they are done in the Temple. Outside the Temple confines, in other areas of religious life, the sensibilities which Nadav and Avihu represent are of value, and are to be cherished. This is what makes them 'greater' than Moshe and Aharon, who, as obedient servants of God, lack their qualities. In the Temple, however, the immediacy and totality of God's overwhelming presence necessitates the obedience of a Moshe and Aharon - there is no room for the creativity and spontaneity of Nadav and Avihu's offering. This is why Moshe and Aharon were not chosen to sanctify the Tabernacle with their deaths - their mode of religious activity is appropriate to the Tabernacle. They have learned to control themselves, and act in accordance with the demands of the immediate presence of God. It is Nadav and Avihu's mode of religious expression, as precious as it may be, which is at odds with the supreme sanctity of the Tabernacle. Their deaths dramatically demonstrate that, and thereby “sanctify” the Temple.

It is important to note, I think, that this entire story is told in the context of fathers and sons - Aharon's grief as a father who has lost his sons, Moshe's comforting him as a brother and uncle, all make this a family story. This would seem to indicate that the issue we have discussed here is a generational one. Aharon and Moshe, the archetypal fathers/founders of the family/tribe/ritual, have a relationship with God and His laws typified by humility, obedience, concern for detail, and letter-of-the-law compliance with the rules. Their children have a more personal, dynamic, from-the-heart (perhaps somewhat rebellious) relationship with the religion and its rituals. This is seen by the 'parents' - God, Moshe, and, in his silent acquiescence, Aharon - as valuable and precious, but too dangerous to be at play in the context of the central rites and rituals of the tribe in its Temple. Their spirit, their religious daring, belongs elsewhere, outside of the center. The Temple is not the place for this strange fire, and, therefore, they must be punished for deviating from religious norms in this holiest of places, thereby making it clear to the rest of the 'children' that such behavior, while at times perhaps of tremendous value, is unacceptable at the very epicenter of the nation's religious experience.

This would seem to present us with an interesting religious and communal challenge: the need to determine exactly where and when such creativity and spontaneity is to be applauded and encouraged in religious life, and where and when it is to be condemned, and a more conservative and normative obedience to traditional religious behavior adopted. One could argue that there are many Temple-like, immutable religious and communal norms that demand unquestioning obedience and absolute loyalty – as the taboo of intermarriage was viewed, for example, during much of Jewish history. Perhaps we need to identify those types of behaviors and beliefs and red-line them as beyond the reach of Nadav and Avihu-like innovation and creativity, and only allow a fresh, personal, subjective approach in areas we identify as less sacrosanct, less dangerous to play around with. This approach could even argue that there are no such areas, and that all of Jewish tradition deserves a Temple-like respect and awe, but that would make it hard to understand the greatness of Nadav and Avihu, and also flies in the face of the entire Rabbinic project.

Alternatively, we could point out that there is not, and never was, anything in Jewish life that has the religious power of the Temple, nothing that, due to the palpable presence of God, demands total, unbending obedience and unquestioning loyalty, to prescribed ritual norms. Since the destruction of the Temple, perhaps all of Jewish life should be seen as the appropriate arena for the from-the-heart, personally inspired, innovative approach which was precisely the greatness of Nadav and Avihu. (It could be argued that we are talking about the period from the destruction of the first Temple, as the second is seen by Jewish tradition as being much less clearly and overpoweringly inhabited by the divine presence. Only in the Tabernacle in the desert and the First Temple was God understood to actually dwell among the Jewish people, and perhaps only in those circumstances are the spontaneity, emotional honesty, and daring of Nadav and Avihu inappropriate.)

If this second understanding is correct, then it is only in the Temple that the absolute adherence to accepted, commanded norms is the right approach. Everywhere and everything else in Jewish life and thought is best approached in the spirit of our tragic heroes, Nadav and Avihu: fearlessly, with emotional and intellectual honesty, from the heart.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Shemini Divrei Torah from previous years