Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

This week’s parsha, Chayei Sarah, has a very obvious, basic, structural problem.

After the death and burial of his beloved wife, Sarah, Avraham turns to take care of the remaining piece of family business: finding a wife for his son and heir, Yitzchak. Avraham does not want him to marry a local, Canaanite, girl, and prefers that he take a wife from Avraham’s hometown, Aram Naharayim (apparently in the northern part of Syria). Although both societies were pagan, Avraham feels that his ancestral home, inhabited by his own kinsmen, is a better place than Canaan for the future mother of the Jewish people to come from.

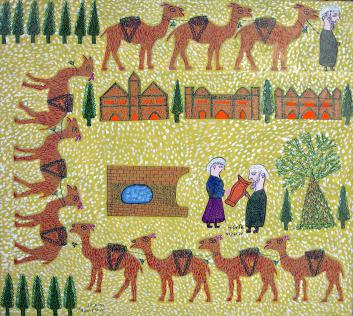

He sends his trusted servant, Eliezer, to perform this task, giving him very clear instructions about where the bride should come from. Eliezer goes to Aram, arrives at the well, and asks God to send him the right girl, stipulating that there is a specific way he will know who she is: she will be proven to be worthy by the kindness and hospitality she will show to the stranger, Eliezer, by offering water to him and his camels.

Rivka appears, and very graciously brings water for Eliezer and the camels. When asked, she reveals that she is, in fact, related to Avraham, and invites him to eat and stay at her family home. His stipulation having been met, Eliezer is sure she’s the one. He thanks God for helping him succeed by sending her his way as he had asked, and goes home with her.

When Eliezer meets Rivkah’s family, our structural problems begin. He tells them the entire story all over again: who Avraham is, his desire to have his son marry a kinswoman, how he arrived at the well, asked God for help, stipulating that he would know he had found the right girl by seeing who would offer him and his animals water, then along came Rivkah, offered the water, he thanked God for answering his prayers; the whole story, which we have already read, and which already has gone on in some detail for quite a while, point by point, leaving nothing out. Just the retelling takes about 15 verses, all of which could have been beautifully summarized by something like “And Eliezer told them who he was, and all that happened to him, with Rivkah, at the well.”

This is a remarkably uneconomical way to tell the story. It is doubly extraordinary for the Torah, which is known for its brevity and downright closed-mouthness most of the time. Why is Eliezer’s story presented in such a long-winded way?

The Rabbis responded to the problem. In the Midrash Rabbah they explain the seemingly unnecessarily detailed retelling of the story by Eliezer this way: God enjoys the everyday conversation of the servants of the patriarchs more than the Torah of their descendants. The story of Eliezer is repeated, as we have seen, while many very basic and essential laws of the Torah are not even clearly stated; only hinted at.

Now this really goes to the heart of the matter, as Rabbinic statements so often do. The Midrash sets up a dichotomy: there is everyday speech, and there is Torah. Looking at the Biblical texts, we do notice that, for most of the first quarter or so of the Torah, what we have is life: everyday conversation, everyday behavior, on the part of the patriarchs and matriarchs, their family members and servants, and the people with whom they interact. Usually the Torah presents these discussions, conversations, and activities fairly succinctly, as it does with the later, legal material which makes up the rest of the Torah. But here, with Eliezer, the narrative gets long-winded, and unnecessarily repeats Eliezer’s retelling of his story. The Midrash tells us that this is to teach us something about the relative value of the regular, everyday speech of the patriarch’s servants, as opposed to the legal material, the Torah, of the children – that’s us - which makes up the bulk of the Torah, and which is, paradoxically, taught with as much brevity as possible, sometimes even through the vaguest of hints. The obvious question is: how can this be so? How can the speech of even the servants of our forefathers be more dear to God – more worth ‘wasting’ Biblical verses on – than the bulk of the Torah’ legal material? What is so dear about it, and what is so unimportant, barely worth mentioning, about the regular Torah?

Well, there is an explanation that speaks in terms of the holiness and spirituality of the patriarchs, as opposed to the later generations of their children. Avraham, Sarah, and the other ancestors of the Jewish people were so God-centered, so morally refined, that not only their own speech, but even the everyday conversation of their servants, whom, we would assume, are only somewhat as spiritual as their masters, is worthy of repetition and, on our part, careful attention and study. The explanation continues: When we do examine Eliezer’s speech, we can clearly see what is so special about it. It is suffused with faith: he is loyal to Avraham, and to the task he has given him, and he believes God will send the right girl his way, and asks for His help. It is full of grace and charity: the girl shows herself to be the one, in Eliezer’s thinking, through her kindness to strangers, and to animals. It is typified by gratitude to God for sending the right girl Eliezer’s way so quickly and clearly.

Clearly, speech like this, a worldview like this, is worth recording again and again, as many times as Eliezer actually spoke it and retold it, and is well worth our attention, study, and imitation.

Well, this is all true, as far as it goes. Eliezer really does show great faith and trust in God, his master, and his master’s destiny. He also has his values right: it is Rivkah’s kindness which will distinguish her. However, I think this understanding misses a big part of what the Midrash says. The Midrash favorably compares Eliezer’s conversation, and the fact that the Torah goes to such pains to record it, with “the Torah of the descendants”, which God apparently has less time for, and so wastes fewer verses on. Now that is saying something other than just “Pay attention to how these people speak, how their speech is suffused with faith, and values, and gratitude.” It is saying that their speech is actually more important that later halachic material in the Torah. It is so important that it is worth recording in any number of verses, while the less desirable legal material sometimes barely merits a mention.

This is not only about the extraordinary faith and God-centeredness of our forefathers and mothers. If that was the issue, the comparison would need to be between their conversations and ours, how special theirs was, how mundane and secular ours is. That is not what is being said here. Rather, I think this is about the relative importance of everyday speech – and action - as opposed to involvement in the legal and ritual material in the Torah. The point seems to be that our everyday activity is what the Torah is really concerned with, and less so with the legalistic aspects and rituals of Judaism. This Midrash is about the dichotomy between life and law; ritual religious activity and real life, and it clearly votes for real life as the place where our faith can optimally be displayed. The place where we really show that we are children of Avraham and Sarah, the place where we really do what God is interested in and cares about, is when we talk, interact with people, go about our everyday tasks, and NOT when we are engaged in narrowly defined “Torah” - ritual behavior. The patriarchs were not only extraordinarily idealistic and God-centered; they were also not burdened, in their relationship with God, with legalism, with ritualized do’s and don’ts. Their relationship with God, and with His justice, happened in the everyday, in their mundane interactions with the world around them, and not only in the sphere of “religion”. This is why God prefers their speech, expressive as it is of their everyday commitment to Him, their trust in Him, and their gratitude to Him for His help, to our “Torah”, our involvement in mandated, scripted, ritual activity. The Torah repeats every word of Eliezer’s conversations because they are such a real, lived, natural expression of his faith and goodness.

We, the children of Avraham and Sarah, burdened by the Torah, by the weight of ritual, must find a way to make that sacred activity real, and meaningful. But most importantly, we need to remember the primacy of the lived religious life, unfettered by specific rules and regulations, but infused with a consciousness of God and His values.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Chayei Sarah Divrei Torah from previous years