Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

In this week’s parsha, Tzav, we are told the details of the rituals connected with the final days of preparation for the opening of the Tabernacle in the desert. There are details about sacrifices, and the rituals which sanctify the Tabernacle itself, its vessels, as well as the priests – Aharon and his sons – for the work they will do in this portable Temple.

One of the rituals which appears in connection with the preparations necessary to sanctify the Tabernacle and everything and everyone connected to it is the anointing with olive oil. The Tabernacle itself, its utensils and structures, the altar, the priests, are all anointed in various ways with the oil – it is sprinkled, shmeered, and poured on just about everything in sight.

What is the point of this ritual? Why is the application of olive oil an act of sanctification, so much so that the priests themselves get the oil poured and shmeered on them, and the Tabernacle is not made holy, and is therefore not functional, until all of this anointing is done to all its elements? What is so special, so holy, about olive oil?

Today, of course, if you asked someone on the street that question, they would probably respond with something about the Mediterranean diet, and the many health benefits of olive oil. Well, that’s all well and good, but no one was ingesting the olive oil in the Tabernacle, they were anointing and being anointed with it. Why was this material chosen as the agent of sanctification?

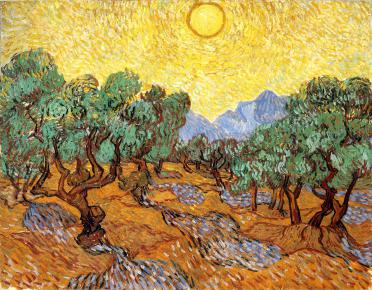

I’d like to suggest a few features that olive oil has which will perhaps help us understand what it means for it to be a sanctifier. First of all, olive oil is fairly ubiquitous. The olive tree grows everywhere in Israel (it is one of the landscape’s distinguishing features), in the entire Mediterranean basin, and, in more recent times, has been successfully cultivated all around the world. It is also ubiquitous, almost magically so, in its uses. The fruit, obviously, can be eaten, and the oil made from it is essential in the preparation of food and, before electricity, in providing light. For millennia, olive wood has been used both in building and in the creation of fine pieces of woodwork. The olive tree is, in fact, a powerhouse provider of our fundamental needs, with its oil, especially, providing most of what is necessary for basic life.

By using olive oil to sanctify the Tabernacle, its vessels, and the priests, we are making an interesting statement about sanctity. Holiness is meant to be life-giving, as is the olive. It is meant to be accessible and useful to all, as is the olive. Rather than seeing sanctity as something rarefied, dark, esoteric, hidden, and intended only for the few, the sanctity symbolized by olive oil is positively democratic, there for one and all to take advantage of, user-friendly, life affirming. It is both a symbol and provider of light, rather than darkness, a supplier of simple, basic, universal needs.

On the other hand, the olives does demand some work. The fruit is really only edible when fermented. The oil needs to be pressed out of the olive itself, and processed. So, although the uses of the olive are many, one can only take advantage of them after some thought, work and preparation; they are not simply there for the plucking.

I would argue that the symbolism of the ritual of anointing is meant to teach us to judge our holy places and activities by the yardstick of the olive and its oil. Are our holy places, people, and practices as helpful and life-giving as the olive? Do they shed light, rather than darkness? Are they as positive and helpful as the olive and its oil are? Do they give, rather than take? Are they good for everyone, uniformly? And do they take some thought, work, and preparation, or do they claim to be instantly and magically available?

The Tabernacle, its furnishings and vessels, and the priests, are anointed by olive oil to teach us that holiness is meant to be healthy. It is meant to do good, to help, as the olive does. It asks us to do some work, but it richly pays us back. A system of sanctity that fails to reward its followers the way the olive does – with life-giving, life-affirming, life-supporting light, is apparently not sacred at all.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Tzav Divrei Torah from previous years