Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

This week we begin the book of Bamidbar, which means “in the desert” – which is where it all takes place. In English it’s called Numbers, as it begins with and contains a number of censuses of the Israelites.

The Sforno comments on this divinely ordered counting of the Jewish people, and compares it to the one that takes place later, towards the end of the book (Bamidbar; 26,2). He points out that the counting in our parsha included each and every Israelite by name, recognizing individual personalities and qualities. The Ramban (Nachmanides) elaborates, and tells us that each Jew was personally met and spoken to by Moshe and Aharon. It was a privilege, an empowering honor, a recognition, to be counted in this way.

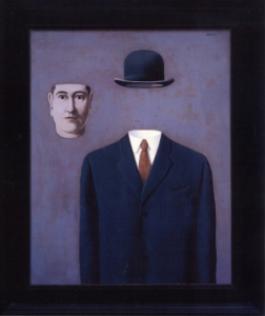

The later counting, which occurs at the end of the forty years of wandering in the desert – which was a punishment for the sin of the spies (their refusal to enter the Land of Israel) – does not work in this personalized way; it is a more general, impersonal, census, in which not everyone is called by name. This, the Sforno says, is the result of the Israelites having been diminished by the sin of the spies. It is as if they are no longer the great, inspired individuals they were at the time of the exodus and the giving of the Torah; they have been reduced, by the sin of their cowardice and lack of faith, to a regular, run of the mill, nation, a basically faceless group of un-individuated components.

This change in their status is reflected by a change in the way the Canaanites relate to them. Had the sin of the spies not taken place, the Jews would have entered Israel just twenty days after our census. The Canaanites, in the wake of the miraculous exodus, faced by a clearly inspired people, would have, according to the Sforno, simply abandoned the land to the Israelites, recognizing the pointlessness of resisting God’s will. Forty years later, however, this was not the case. After the sin of the spies, the sin of being too afraid and insecure to enter the Promised Land, the Canaanites fought, and needed to be conquered militarily by the Israelites.

This dynamic has a lot to say to us about personal and communal identity. Somewhat paradoxically, and at odds with what many people seem to think about what makes nations and communities strong, Israel would have been at its most powerful, and impressive, as a collection of separate, recognizable, individuals; people with names, and stories, of their own. A nation like that, a nation of distinct individuals, would have been too powerful for the Canaanites to even think about fighting.

Forty years later, however, after failing to live up to the awesome potential they possessed as a nation of individuals, they are now only a faceless group, not worthy of being counted by individual name. Such a nation, rather than being strengthened, as some might think, by a lack of individuality, of diversity, is, in fact weakened by it, and is seen by the Canaanites as fightable.

A community is not at its strongest when all its members are reduced to unthinking cogs in a machine. A community, a nation, is strongest when made up of diverse, recognizably different individuals, who are treated and respected as such. It is only then that they are able to be themselves, to bring all of their potential, all of their skills, into play. That type of nation is much stronger than one in which all its members are forced, or have placed themselves, by their cowardice, into a type of impotent group-think, and have been turned into an undifferentiated mass.

Shabbat Shalom,

Shimon

Get inspired by Bamidbar Divrei Torah from previous years