Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

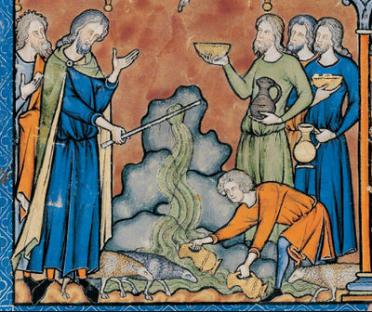

The story of Moshe hitting, rather than talking to, the rock, and thereby producing water, is a vexing one. The various commentaries twist themselves into veritable pretzels trying to figure out what exactly was “the sin”; what was so bad about Moshe’s behavior that, because of it, he was punished by being kept out of the Land of Israel. The explanations, nicely summarized and mostly rejected by Nachmanides in his commentary, include the obvious hitting rather than speaking to the rock (which is strange because God told him to bring the staff, and in the past he used it, once even to hit a rock to produce water!), his angry language towards the Jews (“listen here, you obstinate, rebellious ones”) , and his apparently taking credit for the water as opposed to giving it to God (“from this rock will we bring forth for you water?”).

A simple explanation would, of course, be “all of the above”. Moshe’s frustration with the people’s constant complaining created a negative, rather than positive experience, full of anger, blame, a hint of violence, and perhaps some unnecessary self-justification, which fell way short of the lesson that could have been learned by the people had this miracle been done in the right spirit. It’s not any one thing that is“the sin”, the specific cause of the subsequent punishment, rather, it is the combination of Moshe’s snappish, curt, aggressive and defensive language and behavior that turns the experience into a negative one for the Jewish people.

This reading teaches us an important and difficult lesson about the tragedy of misread communal needs, and missed opportunities for appropriate leadership and role modeling. There may be times when we simply need to get the job done, and niceties such as speaking a certain way or refraining from even symbolic gestures of violence (hitting rather than speaking to the rock) are unimportant, or even counter-productive; sometimes you need to be cruel to be kind - tough, and direct. Moshe’s first public act of leadership, the killing of the Egyptian taskmaster, was all about real violence, and completely devoid of any speech. But now, at the end of the 40 years in the desert, as the nation approached the Land of Israel, a different lesson needed to be taught, a different behavior needed to be modeled.

As the people were about to transition from rebels against Egypt – for that is what the Exodus was, an ultimately violent slave rebellion – and survivors wandering through a hostile desert, to a civil society living in its own homeland, Moshe needed to model a different style of leadership, a different way of running things. The meta-message of his behavior with the rock – anger, frustration, self-justification, and force – was inappropriate for the new leadership style which running a nation state calls for. The 40 years in the desert were meant to refine and mature the people, to allow them to evolve away from respect for power, drama, and even violence, to an appreciation for reason, deliberation, and mutual respect. Although Moshe, as the people of Israel approached the land, still needed to carry a big stick, he should have spoken softly.

The lesson then was that Moshe’s time as leader was up. The lessons for us today, here, there, and everywhere, are many and obvious.

Shabbat Shalom,

Shimon

Get inspired by Chukat Divrei Torah from previous years