Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

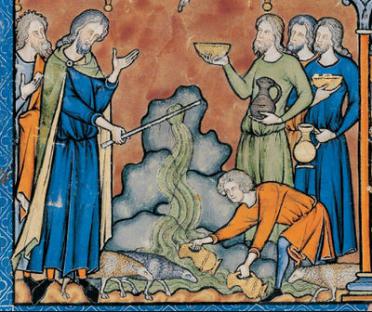

In Parshat Chukat, we read the tragic story of Moshe’s fatal mistake – his hitting the rock, rather than speaking to it, to produce water in the desert for the thirsty people of Israel. Traditionally, there have been two basic ways of understanding what this sin, the punishment for which was to deny Moshe entry to the Promised Land, was really all about.

One popular understanding focuses on his expression of anger towards the Jewish people: “Listen, you rebellious ones, will I take water for you from out of this rock?” The language of “rebellious ones” and the apparently sarcastic, caustic tone of the question indicate anger and frustration at the nation, who seem to never stop complaining. This, according to one common interpretation, was Moshe’s sin; showing anger and impatience, rather than compassion, understanding, and forbearance. His subsequent hitting, rather than speaking to, the rock, is simply a further, physical expression of that inappropriate anger; a failure in leadership, for which he received his awful punishment.

Another traditional understanding focuses more on the hitting of the rock. This reading is based on God’s communication to Moshe after his sin. In this speech, God accuses Moshe and his brother Aharon of not having sufficient faith in Him, and thereby failing to “sanctify Me in the eyes of the children of Israel”. This failure to sanctify God is understood in a Midrash, brought by the 11th century commentary Rashi, in this way: had you drawn water from the stone by simply speaking to it, as commanded, rather than by striking it, the people would have said, “look at that rock, which can neither speak nor hear, and needs no sustenance, and yet it fulfills God’s commandment [by producing water when asked]; should we not certainly do so?!” The lesson learned by seeing the rock give water in response to Moshe’s words would have been one of obedience to God not out of fear, or need, or duress, but out of free will. That is how God is sanctified; when He is freely obeyed. By hitting the rock, Moshe lost that lesson; after all, if someone was hitting me, I would also do what he asked, whether I really wanted to or not, whether it was really right or not. What choice would I have? This was Moshe's failure to “sanctify” God in the eyes of the people. This lost didactic opportunity, missing the chance to teach the Jewish value of free will in our interactions with God, the holiness of decisions made and actions taken freely, rather than out of an unholy fear or power-induced obedience, was Moshe’s sin.

I think we should take a moment to let this sink in. The importance of freely choosing to serve God and do His mitzvoth, rather than acting out of fear or desire for advantage, is so great, so central to Judaism, that Moshe’s failure to teach it meant that he ultimately failed as the leader of the people of Israel, and therefore could not take them to the Land of Israel. The lesson of the rock is that unless we act freely, our actions are not really worth that much, are not really our own. Today, when in our own and other religious communities, anger, fear, peer pressure, even violence – hitting the rock - seems to be the default position for what passes as religious leadership, guidance, and motivation, this is a crucial lesson. If our religious, as well as our moral and ethical, choices are made under duress – “What will the community, my peers, say or do to me?”, “What will my parents say or do to me?”, “What will my religious leaders, or God Himself, do to me?” - then, this story teaches us, these choices are not worth much, they are not really religious, moral, or ethical choices at all.

This understanding of Moshe’s failure also explains a problem we traditionally have with this incident. Years earlier, soon after leaving Egypt, when the people complained of a lack of water, God, in fact, told Moshe to get water for them from a rock by hitting it with his staff. Why, now, is that approach precisely wrong, in fact, sinful? The answer would seem to be that now, years later, as they approach the Land of Israel, the Israelites have matured, and are ready for a more sophisticated approach to faith in, and obedience to, God; one based not on fear of punishment, but on free will, and choice. Seeing the rock obeying Moshe’s words, rather than giving in to the blows of his staff, would have taught the people, and us, that we are meant to obey God by choice, rather than under duress. Our faith in God should be based not on self-interest - the rock, after all, “needs no sustenance” – but on the desire to do the right thing, to be in synch with God’s will. Moshe fails to understand this, perhaps not believing that that kind of faith really exists, or can be counted on, or perhaps thinking the Jewish people are not yet ready for it, and hits the stone. At that moment, this crucial, powerful, beautiful lesson, at just the time that it was needed for the Jewish people, now mature and about to enter the Land and set up an independent society, was lost.

I would like to suggest that these two understandings of Moshe’s sin - a) it was his anger, or, b) it was his missing the opportunity to teach us the importance of exercising our free will in our relationship with God and His commandments - are far from mutually exclusive and are, in fact, complimentary. If we understand that Moshe’s hitting the rock was a symptom, a physical expression of his anger and frustration with the Jewish people, and that hitting the rock also took away its chance to do God’s bidding and supply the water of its own free will, then we are actually being taught that anger is that which denies free will. If someone, especially someone with authority - a parent, a teacher, a communal leader like Moshe, or God Himself (or Jewish tradition and values) – communicates to me out of anger, my ability to freely accept or reject the communication is denied me. It will be my fear, my self-interest, my anger in response, which motivates and drives me, rather than a truly religious impulse. This lack of any real free will renders my response to the anger religiously and morally irrelevant.

As a Rabbi and teacher, as a parent, and, more recently, as a participant in social media arguments, this is a big lesson for me. Anger robs us of what speech is meant to bestow: the chance to express and hear ideas calmly, freely, and willfully. When the focus is on the anger, we lose the chance to really see the issues, respond to them, and act freely and truthfully. We interact with the anger, the self-interest, not with the idea, and the result is the opposite of a willed act. When we are required to make decisions on issues of right and wrong, on the big and little questions we need to answer if we are to live good lives, this is a catastrophic mistake.

Get inspired by Chukat Divrei Torah from previous years