Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

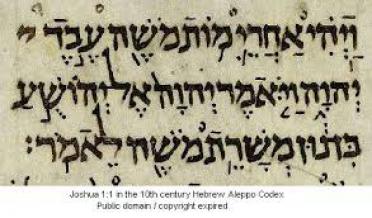

וזאת הברכה (V'zot Ha'Bracha - And This is the Blessing) is the parsha which closes the Five Books of Moses - the Torah - and is read on Simchat Torah. It consists of somewhat cryptic poetic blessings which Moshe bestows on the tribes of Israel as he is about to die and they are about to enter the Land of Israel under the leadership of Yehoshua, Moshe's student. The end of the parsha describes Moshe's death and burial, and ends with a short eulogy, which describes Moshe's unique role as prophet, teacher, and leader.

There are a number of things about these closing verses which raise some questions. The decision to finish the Torah here, and not continue to the real end of the story - the entry into the Land of Israel - is certainly strange. Closing the Torah with Moshe's blessings and death makes it seem as if the focus is the career of Moshe, rather than the story of the Jewish people, which is all about getting to Israel. The final verses are also challenging, especially the way Rashi, quoting the Midrash, understands them, as we shall see.

This last section begins with Moshe going up to Mount Nevo, and being shown the Land of Israel by God: "And God showed him all of the land, from the Gilead to Dan. And all of Naphtali and the land of Ephraim and Menashe and all of the land of Yehuda until the far sea. And the Negev and the plain and the Valley of Yericho, the city of date palms, until Tsoar." What seems like a straightforward description of the borders of the Land of Israel is understood by the Midrash Sifrei, as quoted by Rashi, as something else entirely.

Apparently picking up on the phrase "all of", which is repeated three times, as well as, perhaps, the use of the essentially unneccesary definite article "את", and the choice of places mentioned, the Midrash says that God was actually showing Moshe the various areas in Israel which would be settled peacefully and then come under attack. Again and again, in the areas mentioned, Moshe is shown how the people will experience cycles of war and peace, freedom and oppression. Rather than simply seeing the bountiful and beautiful Promised Land spread out before him, Moshe is actually being given a prophetic history lesson, and is shown by God all the ups and downs, the periods of calm and crisis, that the people of Israel will go through once they have entered the Land. What is the significance of this theme of good times followed by bad, quiet followed by calamity?

After this section, at the very end of the parsha, and of the Torah, there is a kind of eulogy, describing Moshe's unique relationship with God and the Jewish experience: "There arose no prophet since in Israel like Moshe, whom the Lord knew face to face. In all the signs and wonders, which the Lord sent him to do in the land of Egypt to Pharaoh, and to all his servants and to all his land. And in all the mighty hand, all the great awesome things which Moshe did before the eyes of all of Israel." What seems like a clear reference to Moshe as the prophet par excellence, and his role as the savior of Israel in the Exodus story, is, instead, seen by Rashi as a discussion of Moshe as law-giver. Rashi, choosing perhaps trhe least obvious option from the Sifrei, says that the "mighty hand" refers to the fact that he received the Ten Commandments from God in his hands, "the great awesome things" are the miracles done for the Jews in the "great and awesome" desert, and the phrase "which Moshe did before the eyes of all of Israel" refers to his decision to smash the first version of the ten commandments, when the people sinned with the golden calf, a decision God agreed with. Why does the Midrash, which is Rashi's source, force this reading, which relates to the giving and subsequent smashing of the ten commandments , on a verse which is more easily read as referring to the Exodus from Egypt?

It seems to me that it may be helpful to compare the "going up" that Moshe does here - up to Mount Nevo to die - with the other "going up" he did - up to Mount Sinai to receive the Torah, which is precisely what the Midrash and Rashi are refrencing here. That first going up is understood by the tradition as a going up to heaven to commune prophetically with God and learn His Torah - it is as if heaven itself descended on Mount Sinai when Moshe was there. The dynamic is upward, away from the world - Moshe goes up the Mountain, and there relates to an even higher place: heaven itself, and God Himself. Here, in V' zot Habracha, when he ascends Mount Nevo, it is only to look down, on the promised land below. The dynamic of looking down, I believe, does not only relate to the geography of Israel. It is also about looking down from the heights that were achieved on Mount Sinai, where Moshe received God's law, His vision for a perfected humanity living in a state which is in synch with divine law and justice, to the much more prosaic and complicated reality of life in Israel, on the ground, within history. The repetition by Rashi of the theme of Moshe's seeing the various areas in Israel in both peace and war, in states of tranquility and crisis, is meant to communicate the less-than-divine reality of living as a people in a homeland, subject to the twists and turns of the historical process, its inevitable periods of freedom and oppression, its cycle of exile and redemption.

The Torah ends where it does, before the nation enters the Land of Israel, because the Torah is about a more perfect, theoretical vision of what life can and should be than can actually be sustained in the real world, in the land. Moshe, on Mount Sinai, received a model for a perfected society. That is what the Torah is, and it is fitting that it ends where it does, as the model is about to be put into practice. These final verses explain that the model and the reality will not always correspond to one another. As the Torah itself predicts, in a number of places, the Jewish people will sin, will make mistakes, will become corrupt, and, therefore, will be subject to the various disasters which all sinful, imperfect nations face. That story is not for the Torah to tell, it is a disfunction which the Torah warns aginst. The Torah is the attempt to suggest - to demand - something different, a perfected body politic, living according to God's will, while knowing full well that this will not be achieved, due to human nature. The Torah was given in the desert, and ends at the boundary of the desert, where the promised land begins, because it is not really, fully, of this world, the world of reaping, sowing, building and producing, the world of war and peace, conquest and exile.

The choice the Midrash makes, which Rashi quotes, to make the last thing the Torah refer to the smashing of the Ten Commandments, is the clearest possible expression of this gap. Just as Moshe had to smash the tablets as soon as he came down off the mountain, in the face of the sinful, regressive, cowardly act of the making of the golden calf, the Torah itself ends - absents itself - before the people actually enter the land, and the real world. Just as the tablets could not co-exist with the reality of an idol-worshipping people, the Torah, the purest expression of God's will, must come to an end before the Jewish people leave the desert, and God's constant care for them, to enter the land as independent actors, who will understand, be inspired by, and follow the Torah as best as they can but, again and again, will fail to do so fully, properly, and will pay the consequences. This is the message which Moshe is shown by God, when he sees the cycles of peace and war, exile and redemption, that the land and its people will go through.

Years ago, I noticed that a certain tension had developed at our family Shabbat table. My wife and I wanted to discuss the parshat ha'shavua - parsha of the week - with our kids, talk about what they had learned during the week in school, and hear divrei Torah from them. They, on the other hand, (and sometimes me as well), often wanted to read the newspaper and talk about what was in it. I quickly realized that there was a real issue here. In Israel, we are living through just what Moshe was shown by God when he looked down from Har Nevo at the Land: cycles of tension and calm, war and peace, good times and bad. This was Jewish history happening, as we watched. To talk about the parsha sometimes seemed a bit beside the point - perhaps inspirational, but not really that topical - when such momentous and dramatic events - Jewish history in the making - were going on, live and in real time, all around us.

It is this tension between the Torah's theoretical take on how we should be living, and the way Jewish history actually unfolds, that the end of the Torah is dealing with. There is a disconnect between the blueprint, the constitution, which the Torah gives us for the country we will establish in Israel, and the lived reality of that country. The last verses of the Torah stress the unique nature of Moshe's relationship with God, and of his prophecy. He was the one man who could actually bridge heaven and earth, whose hands could actually hold the word of God as written in the Ten Commandments, and who knew that those tablets had to be broken at their first interaction with the often difficult reality of Jewish life. His death, and the close of the Torah, clear the way for a different reality, one in which we consult the Torah, study it, interact with it, but no longer live within it. The text we live in, like the book of Joshua, the first book after the Torah, is, as Moshe sees from the heights of Har Nevo, actual history as it unfolds, life as it is lived, reality as it bites us. Inspired by the Torah, in dialogue with the Torah, but ultimately in our hands to shape, and our responsibility to navigate.

Chag Sameach,

Rabbi Shimon Felix