Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

As someone trying his best to speak reasonably and sensibly about Israel, I am often accused of a whole litany of high crimes and misdemeanors. One recurring accusation is that I am guilty of what-about-ism – deflecting ostensibly legitimate criticism of Israel by, in effect, saying “look over there”, at the horrors perpetrated by other countries around the world, in order to change the topic, rather than deal with Israel’s “criminal” behavior.

I reject this charge. And I’d like to look at Parshat Devarim to explain.

Devarim is always read the Shabbat before the Ninth of Av, the fast day commemorating the destruction of the First and Second Temples by the Babylonians and Romans, respectively. One obvious connection between Devarim and the fast day is a verse in which Moshe, who is just getting warmed up for a Book-of-Deuteronomy-long recap of the past 40 years – mostly not good – recalls having said the following, back in the desert: “How can I alone bear your bother, and your burden, and your fighting?” He goes on to retell that, as a result of his inability to handle the burden of such a difficult people on his own, a judiciary is appointed, and given instructions pertaining to dispensing fair and impartial justice to a litigious, obstreperous, nation.

Moshe’s phrase “How can I alone…?”, in Hebrew, starts with the word איכה –Eicha, a relatively rare form of the word “how” – which is the opening word of the Book of Lamentations, read on the night of Tish’a B’Av: “ How does the city sit alone, that was once full of people?” In addition to the word “how”, there is also the word “alone” which appears, in slightly different forms, in both Moshe’s complaint and Eicha’s opening verse. In fact, the word “eicha” often appears in the Bible paired with some form of the word “alone”. This linguistic co-incidence - the pairing of “how” and “alone”, clearly connects our parsha with Lamentations.

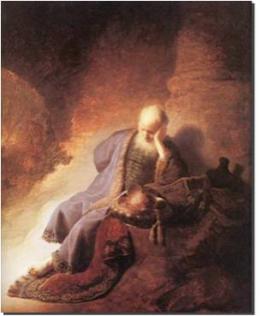

The fact that Jeremiah opens Lamentations by asking, essentially, how it can be that God’s city, Jerusalem, and His land, the land of Judea, are so alone, abandoned and singularly oppressed by other nations, is interesting. Jeremiah will go on to describe awful horrors experienced by the Jews during the Babylonian destruction, and yet he chooses to open with the seemingly less dramatic problem of being alone, marginalized, singled out. Moshe, in his complaint, also stresses how lonely it’s been at the top, how difficult it was for him, on his own, separated from everyone else, set against everyone else, alone.

It would seem that, without diminishing the very real awfulness of physical suffering, the experience of being completely alone, facing an array of enemies – or, in Moshe’s case, problematic, nudgy, complaining people – can be more soul destroying. Jeremiah chooses the sense of being isolated, the experience of being utterly alone, to open his Lamentations, as this, ultimately, is the harshest blow felt by Israel. Moshe, after all he’s been through, feels the same. And the State of Israel, singled out for often false criticism, unlike any other nation, with language usually reserved for Nazis and mass murderers, while far worse crimes are committed daily by a long list of countries, some right in our area, some far away, feels it as well.

When sensible people point out that the Israeli-Palestinian situation is complicated, and not easily reducible to good guys and bad guys, and that, while what Israel does to protect and defend itself is not always perfect or done in the best way possible, our sins are nothing, NOTHING, compared to the horrors perpetrated on a daily basis by other countries, near and far, we are not trying to change the subject, or get people to look the other way; we are trying to show how singular, how disproportionate – not to mention often just plain wrong – much of what passes for criticism Israel is. If it weren’t for the fact that so many gullible, ill-informed and prejudiced people believe the nonsense, much of it would be funny – accusing Israel of Nazi-like genocide and South African-style apartheid while the populations of the West Bank and Gaza (with all the differences between the two – we occupy the one and not the other) grows, goes to college, buys luxury cars, and sits in cafes (more West Bank, less Gaza, but, hey, you had your chance in 2005 and chose murder over prosperity). The singling out of Israel, the unique, exaggerated, and hateful nature of the language used against us, as well as the outright lies, can best be fought by pointing out where we stand on the spectrum of national behavior. I cannot tell you how many college students I have met, in the course of my work, who never heard of China’s ongoing rape of Tibet, or Russia’s actions in Crimea and the Ukraine, but were positive, based on the lies fed to them on campus, that Israel allows no goods at all into Gaza, thereby starving the populace. I have been able to physically show hundreds of people the truth – that some 1000 trucks of commercial goods pass from Israel to Gaza daily - but the lies, singling Israel out for unique condemnation, don’t stop. Pointing out what a real genocide looks like, what a “normal” occupation looks like – rapes and all, which, by the way, are non-existent in our occupation of the West Bank and, in the past, of Gaza – is a necessary corrective.

Israelis today, like Moshe and Jeremiah in the past, ask: How can it be? How can it be that we, alone, are subject to so much vile and disproportionate abuse, while other countries practice slavery, violent racism, colonial conquest, and commit mass murder on a grotesque scale, with nary a peep being heard from the “progressive” community? Why are we, alone, the UN’s and much of the media’s punching bag, with the punches being thrown by some of the worst human rights abusers imaginable? This sense of being alone, singled out, uniquely hated, does not make us feel good or, for that matter, ready for compromise or reconciliation, given the large percentage of the world arrayed against us. It does make us want to teach that part of the world what it feels like to be alone, to be uniquely attacked and maligned for behavior which is relatively benign, and to do that, we need to teach them some context.

Shabbat Shalom,

Shimon

Get inspired by Devarim Divrei Torah from previous years