Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

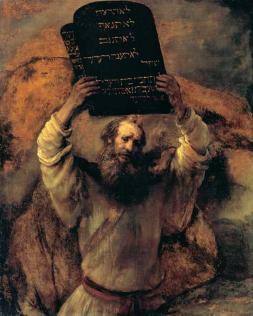

The holiday of Shavuot is a strange one. Unlike Passover, which has a clear agricultural theme – the spring grain harvest – as well as an historical one – the Exodus from Egypt – and Sukkot, which celebrates the fall harvest as well as the assistance and protection God gave the people of Israel during their forty-year trip through the desert, Shavuot, according to the Torah, is only agricultural in nature: a celebration of the early summer wheat harvest and the first fruits of summer. It is only the Rabbis who subsequently reveal to us that this holiday also happens to be the date on which we received the Torah, and that we celebrate that momentous event on this day as well.

The Torah’s reticence about this historical aspect to what is arguably, once we know the history, the most important of the three pilgrimage festivals, is extremely puzzling. Added to this is the weird fact that the Torah does not even give us a specific date for Shavuot – you arrive at the holiday by counting to fifty days from after the first day of Pessach. This roundabout way of telling us the date of the holiday led to some confusion: back when the beginning of a month was determined by actually sighting the new moon, rather than by a set calendar, Shavuot could take place on either the fifth, sixth, or seventh of Sivan, depending on when the moon was actually seen (today, it is always on the sixth). In addition, during the second temple period, the Sadducees disagreed with the Rabbis about how to calculate the countdown (or count-up, actually) from Passover to Shavuot, and had their own way of determining the date of the holiday.

Why? Why is the Torah so unbelievably secretive about Shavuot’s identity as the holiday of the giving of the Torah? Why is the date so unclear, and variable? Why is this pilgrimage holiday different from all other pilgrimage holidays?

It would seem that, unlike Shavuot’s agricultural aspect, and unlike the agricultural and historical aspects of the other holidays, the anniversary of our receiving the Torah needs to be understood in a very specific and unique way. The opaque nature of the content, and the very date, of the Holiday of the Giving of the Torah (the most basic elements of its identity, what it is and when it is), can apparently teach us some important truths about what we celebrate on this day - the Torah itself.

Just as Shavuot is not fixed on a date in the calendar, but, rather, is the result of a process – a counting of 49 days to get to the 50th – so, too, our relationship with the Torah itself is a process, a journey, made up of steps that must be taken in order to arrive at a goal we hope to reach. Just as the date we finally arrive at is variable, and not pre-determined, so, too, is the Torah itself: flexible, ever-changing, to be determined by a journey of study, discussion, and reflection. And just as the date of the holiday could, in theory - and actually did, in the past - fall on different dates, the meaning we arrive at in our Torah study can vary: it can be one thing for you, and your community, something else for me, and mine.

It’s interesting (perhaps “ironic” is the word I’m looking for) that so many self-styled Jewish leaders and educators seem to speak incessantly about the Torah’s “immutability”, “fixed, unchanging, eternal nature”, while what we learn from the slippery date and hidden identity of the Holiday of the Giving of the Torah is the exact opposite: the divinity and eternality of the Torah lies not in its fixed nature, but in its indeterminate aspects. In the fact that it is something that exists only inasmuch as we aim for it, strive for it, and finally discover, on our own, after a process, what it is. Again and again, year after year, journey after journey.

Chag sameach,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Shavuot Divrei Torah from previous years