Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

According to Rabbinic tradition, the holiday of Shavuot celebrates the giving of the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. The commandments are prefaced by the following simple verse: "And God spoke all of these words, saying:" This is exactly what one would have by way of introduction to the words dictated by God to Moshe and the Jewish people. However, the commentaries notice an unnecessary word: had the verse left out the word "all", and just said "And God spoke these words, saying:", we would have assumed that he spoke all of them. After all, "these words" means these words, all the words that follow. Why does the Torah need to emphasize that he spoke all of them?

A simple answer might be that the Torah wants to disabuse readers of the notion that Moshe, or someone else, was actually the author of the Ten Commandments, or of some of them, and so the word 'all' emphasizes the divine source of the entire text. However, Rashi (France, 11th century), does not bring us this straightforward explanation. Rather, he says this: the word 'all' indicates that the first communication from God at Mount Sinai, heard by the Jewish people, consisted of all of the words of the ten Commandments, spoken together, as one sound; "all" means all at once. Now, this is something which, Rashi points out, no human being could do, it is a clearly divine, albeit incomprehensible, communication. Rashi then explains that the word-for-word, sentence-by-sentence version of the commandments written in the Torah - "I am the Lord your God" and the nine others that follow - is what God said next, after the strange, mashed together, all-at-once version.

Well, the obvious question is, why? What is God, a comedian? What is this first communication of all the words of the Ten Commandments spoken at once meant to convey? If God will immediately afterwards speak the commandments normally, one word at a time, what is the message of the jumbled up commandments? Why did God do this strange little parlor trick, and why did the Torah need, with the word 'all', to tell us about it, before telling us the actual content of the commandments?

Perhaps we can understand this first, incomprehensible communication as teaching us this: by prefacing the normal text of the commandments with their all-together-at-once version, perhaps God is modeling for us the nature of Torah study. Just as the Israelites experienced it on Mount Sinai on Shavuot, the first time the Torah was given, as an incomprehensible text, which was only subsequently elucidated, so, too, the Torah must always be experienced as a text whose essential meaning is divine and yet (therefore?) always obscure, not-yet-understood, which challenges us to interpret and elucidate it. The mashed-together version is a model for all of our interactions with the text of the Torah, an interaction which we initially do not understand, and which therefore demands of us an effort to clarify, make sense, interpret, and explain.

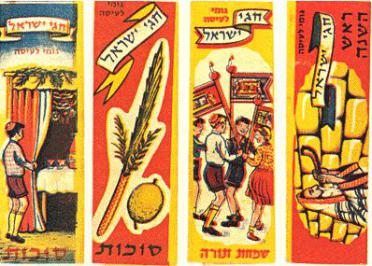

How true or relevant this dynamic is in terms of other, non-Torah texts, be it Shakespeare, a Seinfeld episode or a comic book, is an interesting question, one which is much dealt with by postmodern literary theorists. I'd like to suggest that the greater the text is - the more it is like Torah, the more it is 'divine' - the closer to infinite are its implications, and, therefore, the more it can successfully and meaningfully inspire and bear the endless inferences and interpretations of its creative and active readers. Shavuot, as the holiday of the interpretation of the Torah, is an excellent opportunity for us to rededicate ourselves to being those kinds of readers to those kinds of texts - or to comic books, if that's where your personal literary theory takes you.

Chag sameach,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Shavuot Divrei Torah from previous years