Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

לא, אל תגיד לי מה אתה חושב,

תגיד לי מה אתה מרגיש

No, don’t tell me what you think,

Tell me what you feel

Alon Olearchik, from his song, Tell me What you Feel

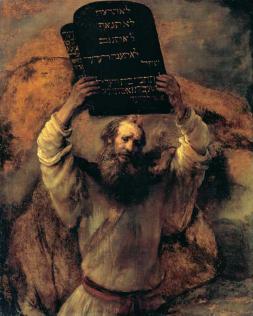

The parsha of Yitro, which contains the giving of the Ten Commandments, begins with an interesting story which serves as a preface to those commandments.

Moshe’s father in law, whom we last saw when Moshe left him in the land of Midian in order to return to Egypt and begin the process of freeing the Israelites, turns up at the Israelite camp in the desert, shortly after the splitting of the Red Sea. When he gets there, Moshe tells him all the things that God did for Israel to Pharaoh and the Egyptians, and how He saved them.

The Torah tells us that Yitro’s response was to be happy. However, a strange word – va’yichad (ויחד) - is used for “and he was happy”. We will come back to that in a moment.

The next verse tells us that Yitro said the following: “Blessed is God (ברוך ה') who saved you from the hands of Egypt and the hands of Pharaoh, who saved the nation from under the hands of Egypt.”

The Rabbis comment on the strange word – va’yichad – used to say that Yitro was happy: Shmuel says [that this word is used] to tell us that his flesh rose up in goose bumps (chidudun – חידודין, a play on the word “va’yichad”). This is understood to mean a response of sorrow, concern, shock; the goose bumps indicate that, while Yitro was happy to hear about the exodus, he also felt – deeply – the pain and loss of the Egyptians. The Rabbis use this fact to teach us to be sensitive to the feelings of those descended from converts, and not insult non-Jews in their presence. In other words, they understand these goose bumps as expressing a personal sense of identification with the Egyptians, on the part of a fellow non-Jew (who has just converted), and extend it to include even descendants of a convert. I will be departing from this understanding of Yitro’s emotions somewhat.

In the Talmud, right next to where this comment about the goose bumps appears (Tractate Sanhedrin, page 94a), there is also a comment about Yitro’s verbal response – “Blessed be God for saving the nation…” It goes like this: “It was taught in the name of Rav Papayis – it is an embarrassment to Moshe and the 600,000 [adult males] with him that they did not say ‘Blessed is God’ until Yitro arrived and said ‘Blessed is God’”.

Rabbi Papayis says the same thing about King Hezekiah – “It is an embarrassment to Hezekiah and his companions that they did not sing a song of praise until the earth opened its mouth and sang a song of praise.” After defeating Sennacherib, the King of Assyria, Hezekiah failed to sing a song of praise to God, though the earth itself did so. This is seen as a failure; a reason, in fact, to disqualify Hezekiah, an otherwise wonderful king, from being the Messiah.

There would seem to be an obvious connection between Yitro’s feeling sorrow and shock at Egypt’s downfall (the goose bumps) and his ability to say “Blessed is God” where others did not. It would seem that Yitro is in touch with his natural, human emotions and instincts, to a greater degree than those around him. Although the Israelites were able to produce a long, complicated, poetic song of praise to God in response to the splitting of the Red Sea, it is Yitro who comes up with the simpler, much shorter, apparently more heartfelt “Baruch Hashem” – blessed is God. Similarly, he is open to feeling shock and sadness, on a visceral level, at the horrible end to which the Egyptians came. Intellectually, he understands why it had to happen, but he remains open to other feelings and emotions, on the most basic human level, and it is his very body – his most basic “self” – which expresses them. This is similar to the “earth “ praising God for the victory over the Assyrians – the world, nature itself sings God’s praises – while, for some reason, King Hezekiah and his people were not capable of feeling and expressing it.

Similarly, the next day, when Yitro sees Moshe busy from morning till night adjudicating the people’s issues, he comes up with quite a simple, practical solution: a system of lower courts. Here again, Yitro is able to come up with a natural, simple, logical response to what he sees. He doesn’t over think it, or ask questions about suitability, precedents, or ask permission- he expresses what he feels when he feels it.

Yitro’s appearing, as he does, just before the giving of the Ten Commandments, may well be a corrective to what receiving the Torah might do to us: render us unable to react naturally, viscerally, emotionally, to what happens to us and the people around us. A system of laws could easily turn us into impotent legal experts, good at figuring out what God’s laws want us to do in a given situation, but without the ability to also respond as people, with our feelings, our natural sensitivities, and our emotions. Yitro comes to the Jewish people just in time, to teach us, as we are about to receive the Torah, to feel, as well as think.

Shabbat Shalom,

Shimon

Get inspired by Yitro Divrei Torah from previous years