Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

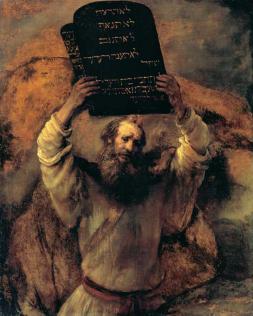

Parshat V’etchanan contains some lovely and powerful verses about the way Israel is, or should be, seen and understood by the other nations of the world, and how we should see ourselves. Moshe says: “Behold I have taught you laws and statutes which the Lord God commanded me, to do these things in the land which you are entering into to possess. And you shall take care and do them for this is your wisdom and understanding in the eyes of the nations, who will hear all these laws and say ‘how utterly wise and intelligent this great nation is’. For who is a great nation, which has God close to them, whenever we call to him? And who is a great nation that has just laws and statutes as all the Torah which I place before you today?”

These verses make it clear that the Torah of the Jewish people, and their relationship with God, are meant to be impressive, to be self evidently right, true, and just. Not only in our, Jewishly trained eyes, but in the eyes of the nations of the world as well.

This idea has some interesting implications. There is a high degree of self-confidence evident in Moshe’s assumption that the rightness and decency of the Torah’s laws will transcend ethnic or national sensibilities, and be obvious to all; he is sure that the non-Jewish world will appreciate the Torah’s greatness. At the same time, Moshe opens the door to non-Jewish assessment of the Jewish condition, of Jewish traditions, society, and legal system, because the clear implication is that if the non-Jewish world doesn’t have such a high opinion of Jewish life and law, then the people of Israel must be doing something wrong because the Torah, done correctly, lived correctly, can not fail to impress.

Now you might ask: well, if that happens, and the Jewish world is critical of, or unmoved by, the wisdom of the Torah, maybe it’s the non-Jews who are getting it wrong; maybe their negative assessment of the Torah is simply mistaken. In fact, when you think about it, many basic Jewish laws – keeping Kosher, ritual bath, the sacrifices, many agricultural laws, etc., etc. – have never been very popular or well received by non-Jews (and many Jews, for that matter). How, then, can Moshe be so sure of gentile approval, when we know that that has often not been the case? Has he forgotten that there are also plenty of anti-Semites out there? The Torah itself talks about חוקים – laws which seem strange, inexplicable, arbitrary, self-contradictory, or pointless, and which, historically, have not been well- received by the non-Jewish world. What, then is Moshe talking about? What approval from the Gentiles are we expecting to see? And what lack of approval from them would be of interest to us? Why would that disapproval, as is implied here, force us to wonder if it is us, after all, who are doing something wrong in our Torah observance?

The Ba’al Haturim (Rabbi Yaakov ben Asher, Germany and Spain, 1269-1343), gives us an explanation. In the words of our verses he sees the following hidden message: of course there will be laws that the non-Jewish world will never get, or like, namely the classic חוקים – seemingly arbitrary statutes with no clear purpose. And so he reads our verses as excluding those laws from the dynamic to which Moshe is referring. (He does this in his usual way, which is with word play (in this case, letter-play): the last and first letters of the words האלה ואמרו רק עם from the phrase החוקים האלה ואמרו רק עם חכם ונבון - “[they will see] these [laws] and say this nation is utterly [wise and intelligent]” spell out various arbitrary statutes, such as מקוה - the amount of water a ritual bath must have to be able to purify - or ערוה , hinting at the strange fact (in the eyes of the Rabbis) that a sister is forbidden to a brother while a niece is not, or the laws forbidding agricultural hybrids.) In other words, the Torah hints to us that the appreciation of the non-Jews for the wisdom of the Torah will definitely not extend to weird ritual and strange, inexplicable, non-rational prohibitions. These laws will be misunderstood, challenged, even ridiculed by the world, and that’s OK. What Moshe is referring to when he emphasizes the universal respect the Torah will garner are the laws that claim to make sense, to be just, fair, compassionate, and decent. Like loving the stranger, caring for the poor and oppressed, dealing fairly in business, not stealing or lying, and giving a good deal of charity. It is this set of laws, known as משפטים – the sensible, logical laws needed to create a just and caring society, to which Moshe refers, and which are meant to be so impressive to the world.

Now this puts a good deal of pressure on us. When non-Jews think that not eating milk and meat together is silly, or that dipping into a ritual bath with a specific amount of water to purify yourself is weird, they are entitled to this position, and it is not supposed to bother us; these laws are not meant to be understood, or applied, or appreciated universally, and not only in a Jewish context. However, when the way we arrange Jewish society, according to Jewish law, in our communities or, better still, in the Jewish homeland (“Behold I have taught you laws and statutes which the Lord God commanded me, to do these things in the land which you are entering into to possess.”), does not produce a just, fair, egalitarian community, and the world sees it that way, then we have failed. If the way we live as Jews, the way we organize our society, doesn’t look wise, and just, and Godly, in the eyes of the world, then we are clearly doing it wrong. Our application of משפטים – the laws meant to be universal, logical, and humane – is subject to the judgment of the world. Moshe was so sure of the wisdom and justice of those laws, and, I guess, confident in our ability to interpret and apply them, that he guarantees the nations will see them for what they are: wise, and just.

How do you think we’re doing?

Shabbat Shalom,

Shimon

Get inspired by Va'etchanan Divrei Torah from previous years