Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

I have to admit that I am not that big a fan of ritual. Of course, some rituals are great, inspiring, a lot of fun, and/or full of meaning, message, or at least nostalgia and aesthetics – like so much of the Passover Seder, for example (I love my charoset, which is the best in the world – just ask my kids). Broadly, however, doing symbolic acts again and again is something I find challenging: sometimes boring, sometimes hard to make meaning out of, often a chore. I really don’t like worrying if my lulav or etrog are in good shape and unblemished. Until they came up with the pre-packaged Chanukah oil lights I hated the olive oil mess. I get bored singing the same songs over and over, both in synagogue and at the table. You get the picture.

I feel that Parshat Kedoshim, the second parsha we read this Shabbat, agrees with me. After weeks of reading about the highly ritualized Temple offerings and services, we finally get to real-life Torah – focusing on charity, loving one’s neighbor, creating a civil society in which we respect one another, especially the elderly, the needy, and the weak. Not ritual, real life.

There is a verse in Kedoshim which expresses the tension between the world of religious ritual, which we just spent so much reading about, and the world of holy, but real-world, action: “My Sabbaths you shall keep, and my Temple you shall fear; I am God.” The juxtaposition of keeping the Sabbath and fearing the Temple generates a good deal of Rabbinic discussion. Famously, it is one of the verses which teach us that we may not break the Sabbath in order to build the Temple, but I’d like to focus on another Rabbinic take on this, from the Talmud, tractate Yevamot, page 6.

The Rabbis there tell us that just as we keep the Sabbath not out of fear of and respect for the Sabbath itself, but out of fear of God, who commanded us to keep the Sabbath, so, too, we should not fear the Temple per se. Rather, we should fear, and worship, and take heed of the God who commanded us pertaining to the Temple. Although the Temple should be treated respectfully and carefully – and there are all kinds of rules about that - it is not the Temple which we are in awe of, it is not at the center of our religious behavior, not the focus of our religious thinking; God is.

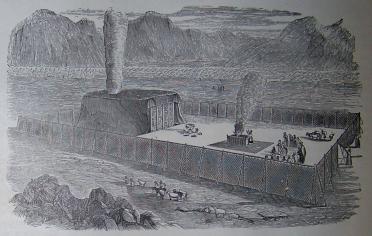

This drasha on the juxtaposition of the Sabbath with the Temple here works like this. Obviously, the Sabbath has no physical manifestation. It is a day of the week, like any other, made special and holy by God’s commandments, by the content He invests the day with. He asks us to use the day to remind ourselves that there is a Creator, a God who took us out of slavery in Egypt, and who demands that we learn from that historical event the need to treat people not as slaves, but as individuals with rights, beginning with the right to a weekly day off for the sake of God, rest, family, and contemplation. That message is what Shabbat is. The Temple, on the other hand, is overwhelmingly physical: the gold, the vessels, the garments, the dramatic and graphic animal sacrifices, the fabulous building. The danger of relating to all that impressive physical stuff with “fear” - seeing it as intrinsically important, as the message, the point - is what we are being warned against here. Just as the Sabbath is a non-physical vessel containing important messages and demanding real-life practices and sensitivities, so, too, is the Temple. Its physical grandeur is not the point, and the physical rituals we are commanded to do there are not what we should be in awe of; the notion of the presence of God, and our relationship with Him, is.

Ritual, which is, after all, a way to communicate ideas and values, can be misunderstood, and seen as having intrinsic value. Our ritual acts are important, as they are the Jewish way to remember, retell, teach (ourselves and others), discuss, understand, and refine issues of right and wrong, truth and falsehood, good and bad behavior. But they are no replacement for the actual behavior itself, they are not what we should “fear” – not what we should ultimately be worrying about. That energy should be spent on figuring out what God thinks is right and wrong, what He wants of us, and doing it.

Shabbat Shalom,

Shimon

Get inspired by Kedoshim Divrei Torah from previous years