Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

In the ongoing conversation/argument about women and Judaism (I know; can you believe this is still going on?) a trope one still hears quite often from the religious right is: “But what is their motivation? Why do they really want to pray together with women (or with men)/read a ketuba/be Rabbis/study Torah so much? Do they really care about the Mitzvah, or is this just an attempt to get something? What they really want is honor in shul (don’t get me started on the childish, ridiculous way men often behave about the honors in shul), respect, professional advancement (again: and the men?), sexual thrills (unbelievable, no? That would be Rabbi Herschel Shachter on those wild women’s only prayer groups and the kinky ketuba reading they like to do so much), or, apparently the worst of them all – to advance some foreign, suspect, non-Jewish, promiscuous, feminist (gasp!) agenda. Once what they really want has been established - Game Over! Their motivation stinks, so they are disqualified. They can not participate in these things – which are invariably, technically speaking, OK halachically, but just not the done thing – because of their miserable motivation, which we, mind readers that we are, understand profoundly and completely without even having to ask.

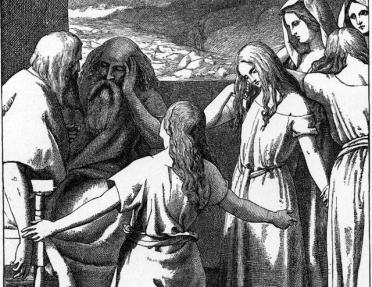

The story of the daughters of Zelafchad in this week’s parsha, Pinchas, should give these folks pause (but I fear it won’t – they apparently have eyes but will not see, ears but will not hear). Zelafchad dies having fathered five daughters and no sons. As the Israelites approach the Land of Israel, and the issue of dividing up and taking possession of the land becomes real, the five daughters approach Moshe and ask if they may inherit their father. Had there been male children, they say, we would have followed the halacha and been fine with them inheriting the rights and possessions of our father. But there are no sons, so may we inherit, and take possession of his share of the land?

Moshe consults with God, gets an affirmative answer, and the daughters get their father’s share, not only of the land but also, as the Talmud points out (Bava Batra, 118b), of their father’s personal property – apparently even Zelafchad’s double first born’s portion of his father’s estate.

Now, if any women could be suspected of having ulterior motives, it is these five. The financial gain is enormous. They were getting an inheritance in the Land of Israel, and their father’s entire estate. And even so, their claim to legal standing, to their halachic rights, was accepted. Yes, I know, you traditionalists out there are thinking “No, it was their love of the Land of Israel, that’s what motivated them, and why they got the thumbs up”, but then what about the inheritance of the parental personal property? And, more to the point, can one not think and feel a few things at the same time? I love living in Israel, I love that there is a State of Israel, and I like my house, I like owning a piece of Israel, all at the same time. Or, for someone who is not me: I like going to shul, and praying, and hearing the Torah reading, and I also like being the one who gets called up to the best parts of the Torah reading, in front of the entire congregation. And this motivational mix is not disqualifying, it is just human.

Let me add another, I think more important, element to the mix. The Rabbis (Bava Batra, 119b) explain that the daughters of Zelafchad put a bit of halachic pressure on Moshe. In presenting their request, they pointed out an interesting anomaly in the legal system: if we are not considered legitimate heirs to our late father, then he was legally childless, and our mother is should have to enter into a levirate marriage with his brother, our uncle – which is what the Torah demands when a man dies without an heir. In this arrangement, in order to keep the deceased’s name alive, his brother marries his widow, and the child they will hopefully have carries on the dead husband’s seed, he is considered his son (an interesting combination of genetics, inheritance law, and some spooky stuff). Now, Moshe knows full well that this is not the halacha – yibum (levirate marriage) only takes place if the husband dies childless; if he had a daughter, then there is no need for a levirate marriage. But he also understands the inherent contradiction in the halachic system that the girls are pointing out: if these five daughters can never inherit because they don’t count halachically as children, then maybe the mother really should do yibum. But if that’s not the law – and it’s not – then these women do exist, they have legal presence, and that should mean that they have the right to claim the inheritance. All of which leads Moshe to go and ask God for some help in figuring this out.

This line of thinking goes to the very core of how we understand the feminist claims on traditional Judaism. There is plenty in the tradition and in Jewish law that makes it clear that women count, exist, have status. This should be sufficient to make us ask, when they seem to be excluded from Jewish life, practice, or ritual, whether that makes sense, whether that’s right. By referencing this yibum question, the Rabbis of the Talmud are teaching us what women’s motivation in claiming status really is: But we do exist, don’t we? If our widowed mother will not need to enter a levirate marriage because we count as our late father’s children, then we are present, from a Torah perspective. That raises the obvious question of where else should we count. Where else do we exist, and, actively or passively, have legal standing, and agency (yes, you can have agency passively; think about it)?

The daughters of Zelafchad wanted to participate in taking possession of the land, and of their father’s property. Their motivations may well have been mixed: a love of the land, a concern for their financial future, a love of their father, a desire to continue the family name, who knows exactly, probably all of the above. But what really matters, what got Moshe to drop everything and go ask God for a decision, was the point they made by referencing yibum: the Torah counts us, sees us, knows we are here. That is enough motivation for us to respond to the Torah’s seeing us, and ask to be seen fully, completely, just like men are.

Shabbat Shalom,

Shimon

Get inspired by Pinchas Divrei Torah from previous years