Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

A Jew is shipwrecked on a desert island. After many long months, he is finally saved. His rescuers are surprised to see two rather large and impressive buildings on the island. "What are these?", they ask him. "Well, that's a synagogue, I built it when I first arrived". "And what's the other building", they asked. "That, that's also a synagogue". "We don't understand, what do you need two synagogues for?" "Are you kidding?", he replied, angrily. "That one, over there, I wouldn't walk into if you paid me!" - Very old Jewish joke.

Two Jews, three opinions. - Very old Jewish truism.

Parshat Pinchas takes place a short time before the death of Moshe. It contains material about dividing the land of Israel, once it is conquered, and choosing a successor to Moshe, Yehoshua, who will do the conquering. That choice is introduced in a very interesting way. Moshe is told by God to prepare for his death, as he will not be entering the Land of Israel. Then, in a verse which the Ba'al Haturim points out is unique, we are told וידבר משה אל ה' לאמר - "And Moshe spoke to God, saying" (it's always the other way around, God speaks to Moshe). What, at this dramatic juncture, does Moshe have to say to God? He asks Him, whom he calls here "the Lord of the spirits of all flesh", to appoint someone to lead the nation. God tells Moshe to take Yehoshua ben Nun, "a man who has spirit in him", as that leader.

The obvious point of interest is what all this "spirit" business is? In the original Hebrew, Moshe calls God ה' אלוקי הרוחות לכל בשר, a strange way to describe Him, and God, seemingly responding in kind, calls Yehoshua איש אשר רוח בו - so what exactly is this רוח - spirit - that all flesh has, which God is the Lord over, and which Yehoshua seems to particularly have, making him the right man to take over from Moshe?

Rashi, taking his cue from the Midrash Tanchuma, explains this "spirit" issue in a way which seems to be sensitive to one of the central problems of leadership. The phrase "the spirits of all flesh" refers to something that leaders need to struggle with constantly: everyone, all "flesh", is different from everyone else. Each person has his or her own personality, their own world view. No two people see things exactly alike, everyone has his own "spirit". Please, Moshe therefore asks, appoint a leader who can somehow deal with all these disparate personalities, who can סובל - suffer, accommodate - all of their varied opinions. God's choice of Yehoshua, as איש אשר רוח בו would therefore indicate that he has within him his own spirit, and is able to accept and accommodate all the other individual spirits of the people.

However, there is an obvious difficulty here. If everyone has his or her own spirit, making leadership difficult, what is special about Yehoshua having it too? Why would that enable him, more than anyone else, to, as Rashi says, "stand up to the spirit of each and every one else"? If the original premise is right, then you could pick anyone to take Moshe's place, as "all flesh" has its own spirit, not just Yehoshua.

It would seem that, although in theory "all flesh" has the "spirit", this may not actually be the case. The explanation that Yehoshua was chosen to lead, and deal with the difficult reality of the diverse and multi-faceted nature of the human spirit, because he, also, has his very own רוח - set of opinions, approaches, and attitudes that are his alone - would seem to indicate that some people, apparently many people, are not like Yehoshua, and have somehow lost this personal, unique, individual take on the world around them. It is apparently exceptional that Yehoshua is איש אשר רוח בו - a man who has spirit in him - that's why he is chosen. The clear implication is that, even though he needs this spirit specifically to deal with the multiple, unique spirits he is meant to lead, he has this quality more than they do, more than the average person, making him the right choice to succeed Moshe. Others, for whatever reason, have not lived up to this basic, God-given human quality, have let it weaken or die within them. Yehoshua has it, in spades.

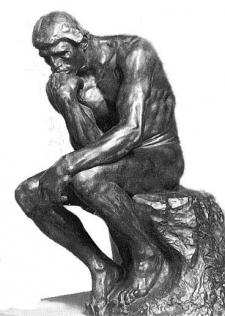

We do not need to look too hard to see how this works. The examples of group-think, of people saying, believing, and acting on the silliest notions simply because they are acceptable, or popular, or current, or official, are myriad. It is, indeed, rare to come across original thought, a truly individual approach to things, and a willingness to go against the tide. Apparently, Yehoshua had these abilities. He, perhaps alone among the Jewish people, fully lived up to the gift we are all given by "the Lord of the spirits of all flesh" - and really had his own spirit, really had a unique way of being in and seeing the world.

Now, the corollary question is: why, and how, does having this talent for, or commitment to, individual, original thinking, make it possible for you to deal with it in others? To rise to the challenge of the multivoiced-ness of people and lead them, hopefully, in one direction? Perhaps having this ability, believing in and privileging this quality, feeling you have the right - the obligation? - to exercise this quality, is exactly what makes one able to accept, deal with, even celebrate it in others. An original thinker, a real original thinker, respects, above all, original thought, and is in a position to respond to it respectfully, seriously, and not fall into the trap of looking for populist or lowest common denominator thinking as an easy way to move things forward. A real leader has, and therefore recognizes and encourages in others, a unique, personal way of seeing things, and understands that that is the best way to lead - by allowing opinions to flow, by encouraging diverse approaches, in an attempt to get to the best one.

I think we should come away from this exchange between Moshe and God about רוח - the unique individual spirit - feeling that it is a mitzvah to have your own opinion. I am not kidding. Although this is a reality that makes it very difficult to lead, or to make communal or national decisions, it is, apparently, a real Jewish value, and the way things are meant to be. I think we would be falling short of the Torah's take on what it means to be a person, and we would be guilty of horribly wasting the spirit we all have within us, if we found ourselves not thinking for ourselves, and agreeing with everyone else all the time. That is not the way we were designed; we are better than that. The old joke and wisecrack at the top of the page indicate how we have come to cherish - while recognizing the difficulty of - this trait. The news we see every day, of fundamentalist, mindless, lock-step thinking, both in our own and in other communities, indicates how dangerous losing this precious gift can be.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Pinchas Divrei Torah from previous years