Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

Over the last few years, visiting the Temple Mount in Jerusalem has become much more acceptable among Orthodox Jews than it used to be. Ten, certainly twenty years ago, only a very small number of traditional Jews thought it was halachically acceptable to go up to any part of the Temple area, basically due to issues of ritual impurity. Today, visiting the area, under Rabbinic guidelines, has become quite popular in Modern Orthodox circles, while at the same time becoming a political flashpoint between Muslims and Jews on the site, and beyond.

In a parallel development, there is a good deal of work going on in preparation for the building of the Third Temple, focusing on the clothing, utensils, furnishings, animals, and other objects connected with animal sacrifice, which, it is widely assumed, will be reinstated if and when the Temple is actually rebuilt, and will be central to its activity.

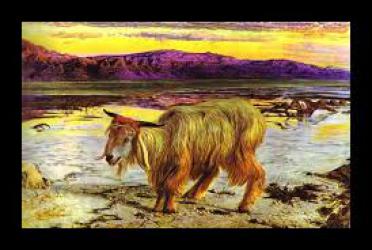

I have always been squeamish about, and morally and ethically uncomfortable with, the idea of animal sacrifice, and find it just about impossible to look forward to. Now, I know that most sacrifices were eaten, making the ritual more of a celebratory feast than an actual sacrifice. I would add that I am not a vegetarian. However, there are a good deal of burnt offerings, which no one eats, and even the peace offerings, which are eaten, contain their share of ritualized blood and gore. Therefore, I would like to bring to your attention some examples of sources within the Jewish tradition which seem to agree with me, and which assume that in the Third Temple we will have evolved beyond the need for this primitive type of ritual.

There is a Midrash on the Book of Leviticus, which we begin reading this Shabbat and which is focused on the sacrificial rites, which clearly states that there will be no sacrifices at all in the Third Temple other than bread offerings - the loaves brought in the Thanksgiving Sacrifice (Vayikra Rabbah, 9; 7, Tanchuma on Parshat Emor, 14). To support this contention, the Midrash brings verses from Jeremiah and Psalms which reject animal offerings.

Maimonides, in his Guide to the Perplexed (III, 32), explains that animal sacrifice was a universal form of worship at the time of the giving of the Torah, and it would have been inconceivable, incomprehensible, for God to attempt to create a religious community without them, as much as He would have liked to. He therefore severely limits this activity, allowing animal offerings only in one place – the Temple – and at certain times and within certain frameworks. The ultimate goal, Maimonides makes clear, is to wean mankind off of this primitive ritual and achieve a more abstract, intellectualized, spiritual worship of God.

The Ramban (Nachmanides), while not, to my knowledge, claiming that there will not be animal sacrifice in the future, does answer a common question often asked by the pro-sacrifice team: If there won’t be sacrifices, what exactly is the point of rebuilding the Temple? Isn’t the offering of animals the whole point of building a house dedicated to God? In his first comment on Parshat Terumah, back in Exodus, when God commands the Israelites to build the very first Temple - the Tabernacle - the Ramban explains that its purpose is to be a place of ongoing interaction between God and the Jewish people; like Mt. Sinai, it is meant to be a place of receiving and learning Torah. He does not mention the sacrificial rites. Only later, in his preface to the Book of Vayikra, does the Ramban explain that the sacrifices serve the purpose of atoning for any sins which might disrupt this relationship. Sacrifices are a kind of maintenance; they are not the point of the Temple, which is an interaction with the presence of God.

Now, we all know that this anti-sacrifice position is not reflected in our liturgy, which, again and again, often quite graphically (mentioning the slaughter of animals, the sprinkling of their blood, and the burning of their flesh), asks for a return of the sacrificial rite. Many Rabbinic authorities disagree with the Midrashim and the Maimonides mentioned above, and instruct us to look forward to, and get ready for, a reinstatement of animal sacrifice. However, the existence of the more forward-looking (in my opinion) sources mentioned above certainly allows, and should inspire, the traditional Jew to choose to prefer a Temple without this ritual, and I happily do so.

The underlying conceptual assumption in these more progressive classical sources – that Judaism seeks to gradually point us in the direction of refinement, sensitivity, and kindness to all creatures (and, dare I say, all people), and that Jewish practice and ritual will adjust accordingly - is certainly daring, and, in my opinion, a crucial piece of what it means to be Modern Orthodox. It is the understanding that Judaism is meant to open the door to an evolving, improving, more progressive sensitivity and morality that must be the center of what Modern Orthodoxy believes in, stands for, and works toward.

Shabbat Shalom,

Shimon

Get inspired by Vayikra Divrei Torah from previous years