Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

Socialism has become an issue in the American political conversation; it has been one here in Israel for a while. The original socialism of Israel’s founders - the Labor party and its various factions - was an essential element in the Israeli economy and society for the first decades of the State. From the late ‘70s, when the right wing under Menachem Begin came to power, and even more so under Bibi Netanyahu’s program of privatization and Milton Friedman/Republican-style economic policies, Israel has, to a large degree, jettisoned much of its social safety net, with predictable results: an ever widening wealth gap, an insane, out of control housing market, high cost of living, low wages, and centralization of wealth and power.

In both the US and Israel, many Jews have embraced the capitalist, anti-socialist approach. This includes quite a few Orthodox Jews, who bring to bear their understanding of Torah laws and values to argue for free markets, unregulated capitalism, and a weirdly Calvinist attitude towards the poor. I remember a few years ago, during the last Shmitta (Sabbatical) year, how some Orthodox thinkers argued against a largely secular attempt to widen the concepts of Shmitta to a broad social justice program, by claiming that the laws of Shmitta – essentially making the produce of the land free for all and forgiving all debts – had no modern application beyond the purely agricultural, and were not really about helping the less fortunate, not really about taking from the rich to give to the poor.

They were, and are, wrong.

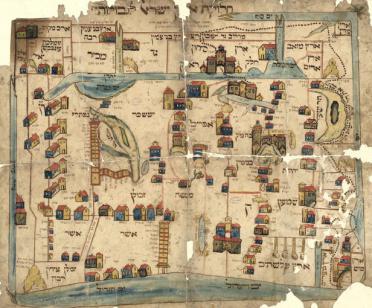

In this week’s parsha, Masa’ei, the nation of Israel is getting ready to enter the Promised Land. One of the things that needed to be discussed was the way that the land would be apportioned to the tribes, once they had conquered it. The Torah says that the land was divided fairly, with large, populous tribes getting more land and smaller ones less. However, the Torah also says that it was divided by lottery, making it hard to imagine how the fairness doctrine – more for larger tribes, less for smaller – was achieved. One would have thought it would be best done by surveyors and demographers, not a lottery.

How exactly the lottery was arranged to make sure this equitable division happened is explained by the Midrash. Broadly, it worked like this: the land was divided into 12 sections, of varying sizes. A lottery was held, and, miraculously, the large tribes won large tracts of land, and the small ones got smaller ones. Not only that, but the size was adjusted, by the lottery, apparently, not only to population but to quality as well – a tribe that got less fertile, less arable, less valuable land, got more of it, as compensation, a tribe that got better land, got less.

The Torah’s demand that the land be apportioned to each according to his need – more land for more people, less for fewer - is taken even further by this Rabbinic embellishment: the equity of the division extends to value, as well as to size.

When we remind ourselves that this division was meant to be permanent, and that if someone was ever forced by circumstance to sell his or her land they would get it back in the Jubilee year, every 50 years, we come to an inescapable conclusion: the Torah wants to distribute the most important unit of wealth – real estate - equally, evenly, equitably, among the Jewish people, and keep it that way. The fact that it takes a miracle – the miraculous lottery – to make this happen, and an adjustment every 50 years - the Jubilee year - to keep it that way, speaks volumes about human greed and selfishness, and the societal drift to inequality. The trend among some halachists and thinkers to try and limit the application of these laws to a no longer relevant agrarian, tribal, pre-modern past, and not extrapolate to our contemporary economy and society, is the height of am haratzut – halachic ignorance.

Shabbat Shalom,Shimon

Get inspired by Masei Divrei Torah from previous years