Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

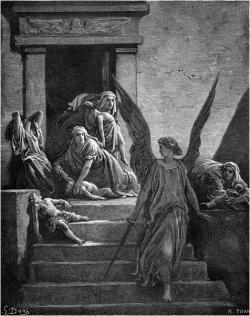

One of the things that have always bothered me about the plague of the smiting of the first born is the fact that all first born sons were killed by God. One could understand this horrible punishment being meted out to the aristocracy, the ruling classes, the landed gentry; after all, they were people who had enslaved and oppressed, for their own personal gain, the Jewish nation. But why did God kill “the first born of the maidservant” and the “first born in prison”? Surely these people, oppressed themselves, were not guilty of oppressing the Israelites – the prisoners were locked up, who could they enslave? Why were they killed in this awful punishment?

Rashi understands the problem, and supplies two answers. About the children of servants he says “and why were the sons of maidservants sons killed? Because they also oppressed the Israelites, and they were happy to see them suffer.” He repeats the second idea, that they were happy to see Jewish suffering, in reference to the first born sons in prison: they, too, were happy to see the plight of the Jews. In reference to the prisoners, he adds another idea: sparing the prisoners would have led people to think that the prisoners’ gods had saved them from the God of Israel. To prevent that theological error, they were killed as well.

The notion that the servants were killed in this plague because they oppressed the Jews as well certainly makes sense. We can easily imagine an Egyptian slave lording it over the even more lowly and downtrodden Israelite. The other two ideas – that these lowly Egyptians were happy to see the Jews enslaved, and that saving them might create theological error, are interesting in a different way.

Unlike the notion that the Egyptian servants actually oppressed the Jews, these other ideas are about a kind of guilt by association. The fact that these groups were happy to see the Jews suffer, or that they would be seen, if spared, to have been save by Egypt’s pagan deities, means that these poor people are guilty because they belong to Egyptian society. Although perhaps not actively oppressing anyone, they were part of a society which did. This made them emotionally just as culpable – they felt and though like oppressors. When we are part of a violent, rapacious, unfeeling society, even if we personally have nothing directly to do with the actual acts of oppression, we become, internally, emotionally, complicit in the crimes. Members of a community are responsible for what that community does. They internalize the warped values and sick mindset of that community, without necessarily actively committing the crimes it is guilty of. They are identified with it, both in their own psyches, as well as by those looking in at them from outside.

The poor, enslaved, imprisoned Egyptians were not members of the class of people who initiated and benefited from the slavery of the Israelites. Nonetheless, they were Egyptians all the same, internalizing Egypt’s values, and identified as members of Egypt’s society and belief system. That is why they could not escape the punishment which Egypt so richly deserved.

Now, take a look at your society, and decide who you really are.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Bo Divrei Torah from previous years