Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

When I was a kid, I used to get completely frustrated with Parshat Chukat. The story of Moshe hitting the rock, rather than speaking to it, in order to supply water for the ever-nudgy Jews in the desert was SO unfair. Back in Exodus (17;6), Moshe, faced with the same whining and complaining about the lack of water, was explicitly told by God to "hit" the rock to solve the problem. Surely, getting a bit mixed up and hitting it again, rather than following the new instructions to "speak to" it, should not merit his being denied the opportunity to COMPLETE HIS LIFE'S WORK (!!) and bring the nation into the Land of Israel! How picky could God be?

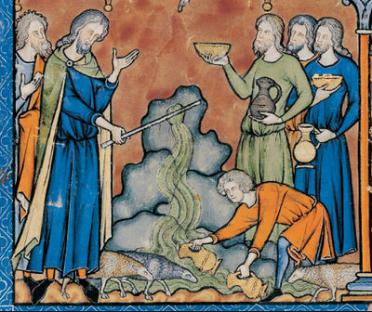

And, of course, the Rabbis only make things worse. The Midrash Tanchuma, quoted here by Rashi in his commentary, tells us that the rock played hide and seek with Moshe. Moshe looked for it, couldn't find it, the people teased him about needing to find the right one - wouldn't any old rock do? - he got mad, tried talking (as he was commanded to) to the wrong rock, and, of course, it being the wrong rock, nothing happened. He then looked some more, found what he hoped was the right one, and, under the pressure of this ongoing fiasco, thought that maybe he had gotten it all wrong, and should hit it, as he had done originally, following God's instructions, back in Exodus, rather than talk to it. He did hit it, and, this being the wrong approach, only a few drops came out. Seeing that some water had appeared, he hit it again, and finally the water flowed. And then God lowered the boom: no Israel for you, you will die here in the desert. I mean, come on! This is so not fair!

Well, I may not be a kid anymore, but this is still quite frustrating, as it really does feel, especially with the rabbinic elaboration to the story, like Moshe is being toyed with, set up. However, I do have some ideas about it. Clearly, the command to speak to, rather than hit, the rock, indicates a maturation, an evolution from a religious model of coercion and punishment to one of reason and persuasion: we don't hit, we talk. Over the 40 years which have passed - we are now just after the deaths of the generation of the desert, and getting ready to approach and enter the Land of Israel - the Jewish people have, hopefully, grown up, and the model of a rock obeying God's will though speech, rather than a whack from Moshe's staff, would appear to be the right one in terms of their obediance to God's will. In other words, the people's relationship to God and his mitzvot has changed: they are ready to respond to reason, not threats, and this is represented by the change in God's instructions to Moshe about the rock - talk, don't hit.

The funny bit (not so funy for Moshe) of the rock playing hide and seek with Moshe can perhaps be understood as being indicative of the changing nature of things: the rock, like the Jewish people, is not in the same place it was some forty years ago. And this is what it was so difficult for Moshe to adjust to. He has trouble finding the rock, as it is located somewhere new, and, rather than meeting the rock's changed location and status with the new approach which God has taught him, speech (I guess if the rock can hide, Moshe can ask it to "come out, come out, wherever you are"), he falls back on the old, tried and true ways, and hits it. And that is the problem: this is no longer the right approach, no longer the way God's commandments should be communicated to the world. But that is a difficult adjustment for Moshe to make: the more things frustrated him because they had changed, and were not what he was used to, the more he fell back on the old religious strategies and modes of behavior, and hits the rock not once, but twice. The transition to the new mode of divine communication with the world, speaking to the rock, was too hard for him to make.

And so, the punishment here really does fit the crime. Moshe can not lead the Jewish people - the new generation of Jews who came of age after the sin of the spies - into the new reality of living independently in the Land of Israel by using his old approaches, and he has proven unable to get behind the new ones. This is the tragedy here, not that Moshe simply lost his temper, but that he failed to respond to the changing religious reality with an approprite adjustment to his behavior as a religious and communal leader.

And this is our tragedy, today, as well. As the world changes, as we change, we dare not simply fall back reflexively, or nostalgically, on "hitting the rock", and rely on the old religious responses to help us deal with new problems and possibilities. We must ascertain where it is we have evolved to - as God and the Jewish people evolved to the mode of speech, rather than violent threats, in their relationship over the forty years in the desert- and calmly come up with the right religious responses to these new realities. We must learn to speak, and not hit, when something new presents itself to us.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Chukat Divrei Torah from previous years