Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

Our social and political discourse, which is always, to some degree, ideological, has become much more so of late. People attack liberal, progressive, right wing, religious, secular, Democratic or Republican positions simply because they are liberal, progressive, right wing, religious, secular, Democratic or Republican, and defend their positions with the same sort of thoughtless sloganeering and reliance on untried and untested ideological claims. They call names, use ad hominem arguments, and often incomprehensible jargon. They don’t really engage in logical thinking or the serious collection and assessment of data, they don’t seek the truth, and they don’t listen; as ideologues tend to, they ignore, and they rant.

Now, there are those who would argue that there is nothing wrong with working out a well thought out ideology and seeing the world through its prism. If you are a Marxist, Marxism is how you understand the world. Whether you are an Orthodox Jew, Keynesian economist, hipster, or a Reaganite believer in trickle down economics and American exceptionalism, it is, obviously, through the lens of your particular world view that you seek to view, and understand, the world. There isn’t necessarily a problem with that.

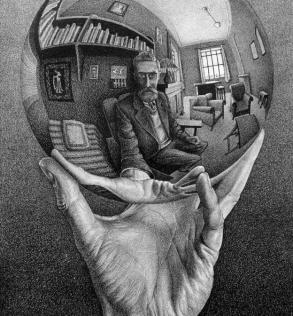

The problem is when that prism, or those lenses (to hang on to both those metaphors) actually function as blinders, preventing us from really seeing the effects of policies, positions or programs we have argued for or against. The problem is that ideology, rather than helping us make sense of the world, can do just the opposite, and prevent us from ever really seeing it.

The anti-hero of this week’s parsha, Balak, is the pagan prophet Bil’am. He certainly has an ideology. Hired by Balak, the king of Moav, along with the elders of Midian, to curse the oncoming Jewish people, as they make their way to the Promised Land, he seems eager to do the job, and help destroy the Israelite nation. He sets out, along with his clients, to do just that. Interestingly, in order to effectively curse them, he needs to go to a high place – the tops of hills and mountains, the edge of a cliff – to look down at and see the nation. Again and again he goes to a high place, looks down at the Israelites, talks about “seeing” them, tries to curse them, and fails, blessing them instead.

The question is why couldn’t Bil’am, who is on the side of the Moabites and Midianites, and sees Israel as an interloper, a conquering army to be defeated, just sit in his tent and say whatever it is he has to say about them? I know I do my best cursing in the privacy of my own home, while reading, hearing, or thinking about this, that, or the other annoying or stupid thing. I don’t need to take a trip to look at the people, positions, phenomena, Presidents or Prime Ministers that bug me in order to curse them; I can do that from the couch.

It would seem that Bil’am is more honest than I am. Before he can curse an entire nation, he needs to go see what they are really like. Bil’am is a real prophet, a חוזה –seer - and he says what he sees, honestly. That’s why he needs to go look at them in the first place; to speak profoundly and honestly about a truth he has witnessed – to prophecy. If what he sees – a nation committed to God, to morality, to its historical covenant with God and the destiny it has as a result - he has to prophecy that; he has to say so. Bil’am teaches us that the truth is out there: it can be seen, understood, and articulated. His inability to curse Israel, once he does see them, is real; the right response, a true prophecy, and not just God literally putting words in his mouth.

Now, here comes the tragedy. One would think that Bil’am, having seen the truth about Israel, its character and destiny, would not simply refrain from cursing them; you would hope that he would actually change his mind, and become a philosemite, a supporter of the Jewish project.

But he doesn’t. Although he admits to his inability to “curse those whom God has not cursed” – with all his climbing mountains in order to look down and see them, he knows the truth – and says beautiful things about them, he still retains his anti Israelite ideology! He still hates them, still sides with Midian and Moab and, as a result, is killed in the Israelites’ subsequent battle with them.

This is a fantastic example of the awful power of ideology. Even when its falseness, or shortsightedness, has been demonstrated, and articulated, and understood, people still hang on to it, revert to it, and insist on seeing the world through it. Although Bil’am was a real and honest enough prophet to see past the blinders of his ideology when faced with the truth of who and what the Jewish people were, he wasn’t strong enough to hang on to that truth. Instead, he immediately reverted to his old position.

The psychology behind this behavior, why we continue to think things that have been seen to be false are true, is challenging. Whatever it is that got us to commit to an ideology, a world view, in the first place, seems to sometimes be stronger than the evidence of our own eyes, our own lived experience, our own intellect. We hang on to these positions in spite of being able to see the truth, for reasons that are, frankly, beyond my ability to completely understand. I guess it has something to do with the tribe we belong to and its beliefs, the comfort we find in thinking what we’ve always thought and being who we’ve always been. Perhaps it's simple self interest, or even our very understanding of who “I” am.

Our challenge is to look at the elements of the real world around us as they actually are, and judge what is working and what is not, what is right and what is wrong, good and bad, healthy or sick, and act accordingly, unimpeded by an ideological lens which is actually a blinder.

Now, you might want to ask me: ‘Well, aren’t you an Orthodox Jew (I plead guilty, though I don’t love that or any other label)? That’s a pretty heavy, all-encompassing world view to schlep around. How can you claim to be any better than Bil’am? Aren't you as blinded as he ultimately was by your ideology?’ I would answer that traditional Jewish law, which is a big piece of our worldview, while often incorrectly described as ‘eternal’, ‘unchanging’, and words to that effect, is actually extremely situational, and quite un-ideological. A halachic (legal) decision is always answered case by case; it depends on who is asking and what their life situation is; it depends on all kinds of specifics of social and economic class, personal likes, dislikes, and sensitivities, local custom and practice, the needs of the community at the time, etc. Beyond the basic ideology of being committed to the halachic process, it is all about seeing a given situation for what it fully is, and deciding accordingly. As the Talmud says (Baba Batra 131a, and elsewhere): “A Rabbinic judge has nothing to consider other than what his eyes see.” Unlike Bil’am, a good Rabbi looks at who and what is in front of him or her and decides accordingly, without a preconceived theoretical or ideological preference, without any unnecessary fealty to precedent or pre-existing assumptions and decisions. Judaism asks of us to look at the real, at the here and now, and make our decisions from there.

Bil’am’s tragedy is that he was willing and able to really look at the world, understand and describe honestly what he saw, but unable to take the next step and change who he was and what he believed in accordingly. Let’s try and do better.

Shabbat Shalom,

Shimon

Get inspired by Balak Divrei Torah from previous years