Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

Here in Israel, we are now living through an interesting period of the year. The weeks stretching from Pessach to Yom Hashoa, Yom Hazikaron (memorial day for Israel's fallen soldiers) and Yom Ha'atzmaut, followed by Yom Yerushalayim, commemorating the liberation of the Old City of Jerusalem in 1967, create a time when one can not help but think about Jewish history, and, most specifically, the role that geography plays in that history. The mistake, in the 1920s, of remaining in Europe once Israel's gates were relatively open to us, the subsequent creation of the state, the price we paid and continue to pay to have our own independant country, the events of the Six Day War and its ongoing aftermath, and the place of Jerusalem in our lives, all of this adds up to a series of questions and challenges about the importance of specific places in our thinking and behavior. This week's parsha, B'echukotay, has something interesting to say about the importance of place in the way we think about Jewish history.

In Be'chukotay we are told what the consequences are if one lives the life of the Torah, or not. Compliance with the laws of the Torah - "if you walk in the ways of my statutes, and keep my mitzvot, to do them" - will result in blessing. Non-compliance will result in a series of awful curses and catastrophes.

The end of the section of the blessings (Vayikra, 26; 12-13), which we would expect to express the ultimate reward for following the Torah's teachings, seems to promise what looks like an enhanced relationship with God: "And I will walk among you, and be to you all a God, and you will be to me a nation." Now, this sounds very nice indeed, but how exactly does it function as our ultimate reward? Isn't understanding that God is our God, and seeing ourselves as His nation, the opening move in our covenant with Him and His Torah, rather than a later stage in our relationship? Is this not a first principle, which we achieved back at Mt. Sinai, rather than the final, ultimate reward for living the Torah and doing the mitzvot?

The Sforno (Italy, 1475-1550) explains that these rewards refer to the days of messiah, when we have fully lived up to the moral and ethical demands of the Torah. He posits that the key here is in the word והתהלכתי - "And I will walk among you...". He says that God's walking among us means walking back and forth, with no specific destination in mind; just being among the Jewish people. He then makes this facinating distinction: this reality, which will be the ulimate state we wiill reach in the messianic era, is unlike previous historical periods, when God's palpable presence was limited to a specific place, the Tabernacle in the desert or the Temple in Jerusalem. Then, God "walked " to one, specific place. In the Messinaic era, God will "walk among you", he will be everywhere among us, as the Sforno says: "wherever the righteous of the generation will be, that will be God's exalted dwelling place." Wherever we live up to the demands of the Torah, wherever we live according to its laws, that is where God will be.

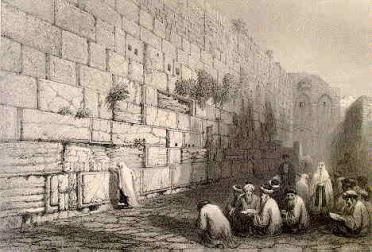

This is an interesting challenge to the idea of a specific holy place - Israel, Jerusalem, the Temple Mount - where God is most present. That idea, powerful and important as it may be, does, obviously, limit God's presence in, and impact on, the world. The notion expressed here, as understood by the Sforno, is that our ultimate hope is to trancend the specificity of holy place and turn the entire world, through the actions of the righteous, into God's dwelling place, God's home, as special as Jerusalem and the Temple, but clearly more accesible, more universal.

The tension between the important, unifying, galvanising idea of a central, sanctified, place of holiness, and the desire to extend that sanctity to the entire world, is one we express every day in the kedusha prayer, when we say "holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts, the entire world is filled with His glory" followed by "Blessed is the glory of God from His place" and "God will rule forever, your God, oh Zion". On the one hand, He fills the entire world with his glory, and yet we also speak of His specific relationship to His place, to Zion. The one sanctity may be in tension with, but is meant to support and sustain, the other.

As we are lucky enough to live, for the first time in almost 2000 years, in a Zion in which God's glory and rule are becoming more and more evident all the time, we need to deal which the tension between that fact and the understanding that the entire world must also be filled with God's glory. We must understand that the special sanctitiy of Israel and Jerusalem can not allow us to turn away from the world, and tempt us to forget that God's will - the demand for justice, morality, respect, love, and high ethical standards - must extend universally, beyond the specific borders and sanctity of the Jewish homeland. Jerusalem, the Temple Mount, Israel, can not be reasons for us to turn our backs on the rest of the world. Their special and specific sanctity must not be misunderstood, and engender within us a negative attitude towards the rest of humanity. Rather, they must be the engines which move us, inspire us, strengthen and propel us, to a greater and greater desire to see God walking here and there, everywhere, wherever we let him in to the world, by behaving and living righteously.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Bechukotai Divrei Torah from previous years