Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

On Thursday - Friday in the Diaspora - we will celebrate Simchat Torah, when we finish the yearly cycle of the reading of the Torah. We will read the final weekly portion, Zot Habracha, and, just as we complete the Torah, we will demonstrate the ongoing, never-ending - infinite might be the right word - nature of the Torah and our study of it, and begin again from the beginning, by reading the first part of the Torah's first portion, Bereishit. Then, on Shabbat, we will re-start the cycle officially, and read the portion of Bereishit in its entirety.

I have always been struck by this strange juxtaposition, on Simchat Torah, of reading the end of the Torah together with the beginning. By the end of Devarim (Deuteronomy, the Torah's fifth and final book), we are at the close of Moshe's farewell address to the Jewish people. After freeing them from Egypt, giving them the Torah, and getting them through forty years in the desert, Moshe stands at the border of the land of Israel, which he will not enter, and blesses the people. He does this tribe by tribe, going through the tribes by name, sometimes referencing events from the past, as well as looking ahead at their futures in the land of Israel: battles they will fight, where and how they will live, how they will support themselves, what activities they will engage in, etc. The portion then ends with Moshe climbing Mount Nevo, and viewing the various sections of the land of Israel, many of which are specifically named. Moshe dies, and then there is a short eulogy, reminding us of Moshe's unique role in Jewish history. And then, every Simchat Torah, we go immediately back, to the Torah's beginning, reading the story of the six days of the creation of the universe, through the seventh day, Shabbat.

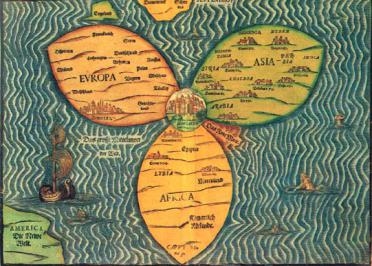

What I find so strange about this is the shift from the end of the story, where we are focused completely on the specifics of Jewish life in Israel - the tribes, where they will live, what they will do and what will befall them - to the creation story, which is so universal - literally! - in its sweep. The creation story, all through the first two portions of Bereishit and Noach, is not specifically Jewish at all. It is a kind of universal pre-history, telling us about the creation of the world, of man and woman, the expulsion from the Garden, the murder of Abel by Cain, and the sins of the entire world, which are punished by the flood, from which Noah is saved, to father the human race anew. We are forced by the juxtaposition of the end with the beginning to rewind, as it were, going from where the Torah has taken us - the story of the children of Abraham, how they became the Jewish people and inherited the Land of Israel - back to the very beginning, where the focus is universal, and the topic is all of mankind.

Reading these two sections of the Torah - the very last and the very first - in juxtaposition, communicates two opposing viewpoints, two very different foci - the particulatristic and the universal. On the one hand, by the end of the Torah, we have come to the tipping point of our specific national history: the Jewish people are a nation, with a unique covenant with God, who, through Moshe, has given us a constitution - the Torah. We are poised to enter our ancestral homeland, which was promised to, and lived in, by our forefathers, and, using that constitution, create a Jewish nation-state, separate and different from the peoples around us. We read that, and then, immediately, we bounce right back to the beginning, to concerns that are universal in their scope: the creation of the world, the nature of sin, the contours of the relationships between men and women, parents and children, siblings, the individual and God. All of these universal issues are right there in the beginning of the Torah, on a canvas as broad as all of humanity, all of creation, and not at all limited to one people.

Reading these two texts together forces us to focus, at one and the same time, on what must be the twin poles of our concerns. On the one hand, it is certainly true that we are a particular people, with our own language, homeland, culture, set of laws and customs, values, and specific history. The bulk of the Torah details that history for us, and the climax of that history, as we are about to enter our homeland, is how the Torah ends. However, at the same time, we are also the children of Adam and Eve, and of Noah, living in a world God created for us all, Jew and non-Jew alike. A world in which we all must struggle with the challenges of how to relate to God, His world, and our fellow men and women. A world that is not, first and foremost, all about being Jewish, but, rather, is about being a human being, one of God's creatures, whom He brought into existence and continues to sustain and judge. The beginning of the Torah teaches us that we are all sons or daughters of the first man and woman, who somehow sinned, were expelled from Eden, sinned again, and, through Noah, were given another chance to live in God's universe. This is our shared, universal, history. It is also our shared, universal, ongoing reality.

Simchat Torah gives us the opportunity to transcend the linear nature of the Torah's narrative, and be in two places at once: the very Jewish last moments of Moshe's life, as he prepares the tribes of Israel for a future in the land of Israel, and the completely universal first days of the creation of the universe, and of mankind. Our task is to hold on to these two very different ends of the Biblical narrative, and live on both poles, in both places, at once; the particulaly Jewish and the completely universal, to be both Jews as well as human beings.

Would you like some suggestions as to how one might pull off this trick of being in these two very different places at once? Well, here's one: as we are starting the Biblical cycle anew, why not commit to studying the weekly portion? That's a very Jewish thing to do. At the same time, how about acting on some of the universally relevant issues raised in the weekly portions, issues that affect us all. For instance: in Bereishit, we have the creation of the world, and a beautiful description of how all the elements of God's creation connect to and interact with the others: the sea waters bring forth life, the land enables plant growth, which sustains the animals and man, etc. As we are busy destroying this perfect balance by causing disasterous climate change, how about doing something about it? Write a letter, walk rather than drive, turn off some lights or some heat, support solar energy, do something to save the planet God created and we are ruining! In the next parsha, Noach, we read of a flood which destroys the world. There it is again, global warnming and the rising of the sea levels! Do something about it. Call up a congressman, or buy a Prius. Alternatively, there is this: in Noach we read about Noach's unfortunate drunkeness, which leads to some sort of very uncomfortable interaction with his son, Ham. Why not get involved with an organization that works on helping people with addictions, or protest aginst the addictive sugars and other added junk in our food. Or how about, inspired by how the sins of Noach's generation led to the world's destruction, doing something to fight any one of the various evils (take your pick) which are destroying our world. ISIS, anti-Semitism, wage inequality, racial discrimination, texting while driving, or driving drunk, God knows there are plenty to choose from.

Good luck with it. We can do this. We can live inside the Jewish bubble of Torah study and mitzvot, Shabbat and holidays, synagogue and prayer, and also change the world. All we need to do is keep one eye on Zot Habracha, and one eye on Bereishit, and live the Jewish, tribal, Torah life, while we interact meaningfully with all of creation.

Chag Sameach,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Bereshit Divrei Torah from previous years