Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

Since the disastrous presidential election, I’ve seen a lot of discussion about what contexts might be appropriate or inappropriate for “talking politics”. Many seemed to be nervous about what might happen around the Thanksgiving table – a problem we here in Israel didn’t have - and the question of whether the Rabbi’s sermon, or the synagogue in general, were appropriate frameworks for political talk was often raised. Many seemed to feel that politics should be kept out of shul, away from the family meal, and off the Rabbi’s agenda at this very difficult, divisive time.

I’m not at all sure that that’s the right approach.

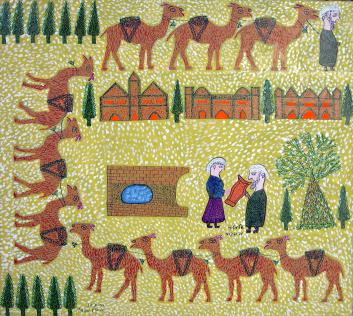

This week’s parsha, Chayei Sarah, tells us the story of a trip taken by Avraham’s servant, Eliezer, from Canaan back to Avraham’s birthplace, Aram Naharayim, in order to find a wife for Avraham’s son, Yizchak. The story is one of the longest in the Torah, mostly because it repeats itself: First Eliezer, when arriving at his destination, asks God to be kind, and show him a suitable wife for Yitzchak. He describes to God exactly what kind of girl he hopes He will send him, and how he will know it is her – she will act generously and kindly towards him, a stranger, when she sees him at the well with his camels. Then the Torah tells us that that is exactly what happens: Rivkah comes to the well and generously supplies water to Eliezer and his animals, and then graciously invites him to her family’s home. Once there, Eliezer tells the entire family the whole story again, how he asked God to send him a kind-hearted, generous woman who would be his master’s wife, and how, just after asking this of God, his prayers were answered, and Rivkah appeared, and behaved in exactly the gracious way he had hoped she would. In all, we basically hear no less than four times the details of how Eliezer stipulated kindness and hospitality as the character traits he was looking for, and that God, in His loving-kindness, sent Rivkah to him, and she then proceeded to exhibit precisely those traits.

The Rabbis of the Talmudic period were sensitive to all this repetition, and especially to the fact that it is something fairly prosaic and humdrum – what the servant Eliezer thought and said about his mission – that gets repeated again and again. In the Midrash Rabbah, Rabbi Acha says: “The speech of the servants in our forefathers’ households is more beautiful than the actual laws of the Torah of the later generations. The story of Eliezer takes up two or three whole pages, and it is repeated again and again, whereas the laws of the forbidden foods, which are basic to the Torah, such as the impurity of the blood of a non-kosher creeping animal, are only learned by a hint from the text.”

Rabbi Acha points out the obvious imbalance between the often very brief treatment which many of the actual laws of the Torah receive, and the long, detailed, repetitive telling of the story of Eliezer’s mission. One would have thought that the opposite should be the case: these Torah laws are what we live by, they create what Judaism and Jewish life is, whereas the stories about our patriarch’s servants can’t have that much to teach us. Why does the Torah spend so little time on the one, and so much on the other?

Rabbi Acha points to the “beautiful” nature of Eliezer’s speech as an explanation to this apparent discrepancy. Yes, it is true, the laws and details of ritual law – what is pure and impure, kosher or not – are crucial to what Judaism is; they are how we live our particularly Jewish lives. Real spiritual beauty, however, that which is of ultimate religious value, and is therefore worthy of page after page of text in the Torah, is not to be found in the legal content of the Torah and its laws. Rather, it is the lived and felt way in which we experience God and His kindness, and participate in and appreciate parallel acts of human kindness – the essential elements of Eliezer’s story – that the Torah is really impressed by, and that Judaism is really concerned with.

Eliezer’s emphasis on his hopes for God’s loving-kindness in support of his mission, and his privileging graciousness and generosity as the attributes necessary in a bride for Yitzchak, are lessons upon which the Torah is happy to “waste” a few pages. It is these attributes, and these actions, which we really need to learn, and learn again. The legalistic binaries of Kosher or treif can be dealt with in a few words, or even less; living a life of kindness, graciousness, and concern for the stranger, is what we need to go into in detail.

There is no more relevant place for “political” discussion – talk about how our lives should be lived, how we should behave towards one another, and what our values should be – than the synagogue, the pulpit, or the Shabbat table. Real Judaism is not the inward-looking focus on ritual and legalism. The real “beauty” of Judaism, the story of Eliezer teaches us, is to be found in the way its values inform our mundane, prosaic, quotidian activities. It is in the real, the secular, the everyday, that we must place our Jewish energies. Just as the Torah is precisely the place where we need to be taught, at length, that it is in the way we conduct ourselves in our daily activities that the beauty of Judaism is to be found, so, too, the synagogue is precisely the place to discuss how we should be behaving in our everyday, secular, political lives. That is where the highest values of Judaism, as expressed by Eliezer, really matter.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Chayei Sarah Divrei Torah from previous years