Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

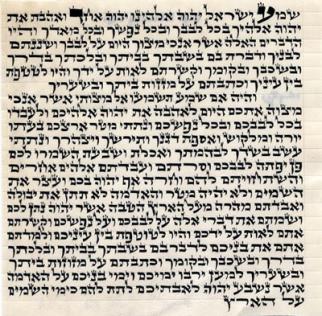

This week's parsha, Eikev, is the third in the book of Devarim (Deuteronomy). It contains a section which is recited daily in the morning and evening prayers, as the second paragraph of the Shema. In the Torah, it appears a few chapters after the first paragraph of the Shema, which is in last week's parsha, Va'etchanan. In it, we have the basic statement about our belief in reward and punishment. It describes how our listening to and obeying the laws of the Torah will be rewarded with God's blessings, in terms of a bountiful harvest, and how failure to obey the covenant will lead to God's anger, and a witholding of blessing.

Both the first and second paragraphs, though separated in the Torah by a number of chapters, clearly do parallel each other. This connection is evident in the last part of each paragraph, in which we are told, in slightly different versions, to write these words in our tefillin, teach them to our children, "When you sit in your homes, when you walk on the road, when you lie down and when you arise." Both sections conclude with the commandment "And you shall write them on the doorposts of your homes, and in your gates." Exactly what "words" we are meant to teach our children, put in our tefillin and our mezuzot, is a matter of some discussion. Broadly, it could refer to all the words of the Torah, or to the specific messages of these two paragraphs, the first two sections of the Shema: the existence and oneness of God, our dedication to His Torah and mitzvot, and the fact that He rewards and punishes us for our actions.

I want to note that the final line of both of these paragraphs is the mitzvah to put "these words" in the mezuzot on our doorposts. I also want to point out that in the second paragraph, here in Ekev , there is an extra, final verse, just after the mention of the mezuza, which says: "In order that your days and the days of your children will be multiplied on the land which God swore to your fathers, as the days of heaven on earth." A simple way to read this final verse would be to understand it as relating to the contents of the entire paragraph: keep the covenant, do all these mitzvot, and you will be rewarded with long life. However, the Rabbis read it as referring to the last phrase, the one about putting up mezuzot, and that the promise of a long life, in the land of Israel, is specifically a reward for doing the mitzvah of mezuzah. In fact, they learn from this verse that women are obligated to put mezuzot on the doors of their houses. The thinking is this: if the mitzvah of mezuzah gives long life, certainly women should be given a chance for that reward, so the mitzvah is relevant for them as well.

Now, this is a nice, egalitarian reading, but the question clearly must be asked: why, among the mitzvot of learning and teaching Torah, putting on tefillin, belief in God and His providence, is the mitzvah of mezuzah singled out as the one that grants long life? Surely it would be better to read this final promise as referring to the entire package of Torah and mitzvot discussed here. Perhaps such a reading is rejected because it would mean that, to be fair, and give women a chance at longevity, they should be obliged to keep all the mitzvot, and the Rabbis, not as egalitarian as all that, believe that that is not the case, so they read the promise as referring only to the mitzvah which immediately preceeds it, mezuzah, which women are obliged to do. But we are left with the difficult notion that, alone among all these basic, seminal mitzvot which we are commanded to do here, it is specifically that of mezuzah which is rewarded so magnificently, with long life in the promised land. Why?

If we take a broader look at the two sections which demand, among other mitzvot, that we keep the mitzvah of mezuzah, we find something interesting. In between the two paragraphs, at the start of parshat Ekev (Devarim; 7,26), we have another mention of ביתיך "your house", the word which appears both times that we are told where we are meant to place the mezuzah. In this intervening verse, we are told something very different about our homes: "Do not bring an abomination into your home (אל ביתך) , or you will be cursed, like it. You shall abhor it, and detest it, for it is a cursed thing." This "cursed thing" is, of course, idols and the trappings of idol worship. The Torah warns us against allowing any physical manifestation of paganism into our homes. God has brought us to the land of Israel, as the final step in our becoming His people, the people who live according to His laws and His covenant. As such, our homes are especially important, and vulnerable. The trappings of idol worship, an idol worship which is all about the fear and awe people feel before the forces of nature, and their childish, mechanistic attempts to control those forces, have no place in a Jewish home. Our homes are represented by the mezuzah, which contains the words of the One God, who created the universe, and who relates to it through covenant, law, justice, and the word, rather than the bloody, frightening, mindless forces of blind, unthinking nature.

Once we are in our land, we are commanded to live by the covenant. Life happens in the home, and it is there that the Torah expresses a particular sensitivity to the way we identify our homes, both to ourselves and to others, as being Jewish. (I might get into trouble if I mention that the home is, classically, more the domain of the mother than the father, which explains why this mitzvah is singled out as being obligatory for women as well, so I won't say it). Paganism, which is ultimately about power and fear, must be kept out of a Jewish home. A Jewish home is noticeable immediately by the presence of words, the words of the covenant, in the mezuzah; the first two paragraphs of the Shema, describing our faith in, love for, and ongoing relationship with, God. The promise of long life in return for keeping the mitzvah of mezuzah makes perfect sense. If our homes are Jewish, and are about a dynamic relationship with a God of love, a God of dialogue, a God who demands multi-generational learning and study, a God of justice and fairness, a God of covenant, then we will have created a successful, coherent, Jewish society. Doing that is the best guarantee for remaining in our homeland a very long time indeed.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Eikev Divrei Torah from previous years