Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

Parshat Lech Lecha marks a turning point in the Torah. The focus is now completely on Avraham and his family, who will become the Jewish people. We follow Avraham as he goes, at God's bidding, to the Land of Canaan, which he is told will be given to his descendants, who will bring a blessing to all the families of the world. Soon after his arrival in Canaan, a famine then grips the land, forcing Avraham to seek sustenance in Egypt. He does well there, and returns to Canaan a wealthy man.

During all of this time, Avraham is accompanied by two people, his wife Sarah and his nephew Lot, the son of his late brother, Haran. Lot goes with him from their homeland to Canaan, then goes down to Egypt with him, and, having become wealthy along with Avraham, returns to Canaan with him. At this stage Avraham is childless; in last week's parsha, Noach, we are told that his wife is barren, which makes Lot a candidate to be his heir, as he is the only family he has.

Upon their return to Canaan, we are told that, due to their many sheep and cattle, the land was too small to sustain both Lot and Avraham. This makes perfect sense: grass-land for grazing, and water, are neccessary for their flocks, and living together means that they will quickly exhaust the limited resources available to them. Sure enough, we are told that "there was an argument between the shepherds of Avraham and the shepherds of Lot, and the Canaanites and the Prizites then dwelled in the land." The Torah does not go into too much detail, but it seems clear that the pressure of finding sufficient grazing land and water was too much for the two wealthy men, and the presence of Canaanite nations may well have exacerbated the situation.

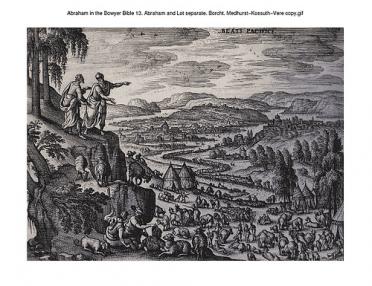

Avraham then approaches Lot and asks that there "not be an argument between me and you, between my shepherds and yours, for, after all, we are brothers." Avraham suggests that they part, and offers Lot the chance to choose whatever land he wants. Lot picks the Jordan river plain, an area that, we are told, is extremely lush and fertile. It includes the cities of Sodom and Amora, whose citizens, we are informed, are extremely evil and sinful. Lot chooses to settle there anyway. This, of course, will figure prominently in what happens next to Lot.

First, there is a war, between the four kings and the five kings, in which the kings of Sodom and Amorah are defeated, and Lot is taken captive. Avraham then goes to battle to save him, after which Lot returns to Sodom, from which he is subsequently saved by God when He destroys the sinful cities. At that point Lot's daughters (his wife was out of the picture, having been turned into a pillar of salt while escaping the destruction), thinking the entire world has been wiped out and that they are the last people on earth, get Lot drunk, sleep with him, and conceive the children who will be called Amon and Moav. After that, Lot disappears from the scene, though the nations of Amon and Moav later interact with the Jewsh people. In fact, King David is decended from Ruth, a Moabite woman who converts to Judaism.

What shall we make of Lot, and his strange history? It certainly seems sad, and disappointing, that Avraham's first disciple, blood relative, and only potential heir, goes "off the derech" (off the path), and leaves the Jewish people behind, all, apparently, over an argument about grazing rights. Let's take a look at the fight between the shepherds, which triggered the initial separation, to get a better sense of what might lie behind this tragic story of the loss of Lot .

Rashi, quoting the midrash, tells us that there was actually a bit of halachic disagreement (a dispute about Jewish law) between the shepherds. Lot's men allowed their animals to graze on other people's lands. Avraham's men admonished them for this act of theft, to which Lot's men replied: "Didn't God promise this land to Avraham? And isn't Lot his only heir? The land, then, rightfully belong to us!" To this, Avraham's shepherds answered that the time for that promise to be fulfilled had not yet come, which is what the Torah is telling us by reminding us the that "the Canaanite and the Prizites then dwelled in the land" - they were still the rightful owners, and Avraham's descendants would have to wait until they would be given permission by God to take it from them. Avraham's shepherds were right, and it was theft for the shepherds of Lot to steal land and resources from the Canaanites.

We see from this discussion that Lot's men were acting from Jewish motivations. They saw Lot as Avraham's rightful heir, to whom the land legally belonged, based on God's promise to Lot's uncle, Avraham, and acted on that belief. Lot was not acting in a way that negated or denied his connection to Avraham, he was just interpreting that connection incorrectly, selfishly, prematurely.

This being the case, we can understand what happens in the rest of the story as actually being about the issue of how we should deal with Jews who deviate from the tradition's expectations, who fail to live up to its understanding of right and wrong. When faced with Lot's bad behavior, Avraham's first response is to ask for a separation - he can not have Lot, who is identified as his kinsman and heir, behaving inapropriately; he must leave. However, Avraham still remains commited to Lot as a brother, and goes into battle to save him when Lot is taken captive. God also sees Lot, even though he has chosen to live in sinful Sodom, as still being part of Avraham's family, and saves him from the destruction of the city. It would seem that wayward nephews, or sons, sometimes may need to be asked to leave the family circle, in order to keep clear what is right and what is wrong, what is acceptable or unacceptable behavior, but they remain members of the family, to whom we must give help when they need it. Wayward sons may need to be disciplined, or even, to some degree, cast out, but they remain sons.

Actually, one wonders what would have happened had Avraham found a way to be more accepting and understanding of Lot's position, and had not asked him to go away. After all, it was only when he was rejected by Avraham, over a misinterpretation of God's promise of the land, that Lot chose to turn his back on Avraham's values and go to Sodom. Perhaps he would have remained true to Avraham's core beliefs had Avraham been more lenient with him, and been able to keep Lot with him, in spite of his actions. Maybe the rejection, as partial as it was, was a mistake.

The fact that, ultimately, Lot re-enters the Jewish people through the conversion of his descendant Ruth, and her marraige into Judaism, underscores the tradition's desire to not completely cut off our wayward sons, but rather to find a way for them to come home. Ruth's conversion and marriage to Boaz represent a final homecoming for Lot - initially sent away by Avraham for his unacceptable take on Jewish values, but never completely abandoned by him, or by God.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Lech-Lecha Divrei Torah from previous years