Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

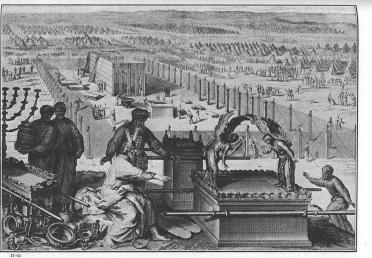

With parshat Pekudei, we complete both the Book of Exodus and the construction of the Mishkan, the portable Tabernacle which seved as the Israelite's temple in the desert. The climax of the parsha, and one of the high points in Moshe's role as the leader of the Isaelites, comes as all of the various elements of the Tabernacle are finally constructed, brought to Moshe, and the Mishkan is finally erected. The report of these final, climactic moments, is interesting, and, I believe, has much to tell us about leadership, service, and our obligation to change the world.

The parsha tells us - quite a few times, actually - that the Israelites had done an extremely good job of donating all the materials needed for the Tabernacle and its vessels, and of actually constructing all of these elements. After that has been made perfectly clear, we are told that "they brought the Tabernacle to Moshe, the tent and all its vessels...". The parts of the Mishkan and the vessels are then listed again, we are once more told that all was done satisfactorily, and God then tells Moshe to actually raise the Tabernacle on the first day of the month of Nissan.

We are subsequently told that "on the first day of the first month the Mishkan was erected. And Moshe erected the Mishkan...". The double language - "the Mishkan was erected...and Moshe erected the Mishkan", in addition to the verse that describes the Israelites bringing all of the completed components to Moshe (rather than just finishing the job of constructing it themselves) prompt Rashi to tell us the following: "The people were unable to raise up the Mishkan, and since Moshe had not done any work on the Mishkan (!) God left the final act raising it up to him, for no man could raise it up, due to the weight of the beams, for no man has the strength to raise them up, and Moshe raised them up. Moshe said to God: 'How can it be raised up by a man?' He said to him: 'move your hands and it will look as if you are erecting it', and it actually rose up on its own. That is what is meant by 'the Mishkan was erected' - it raised itself up."

This description by Rashi, based on the Midrash Tanchuma, offers us some remarkable insights into leadership, service, and the attempt to make the world a better place - to bring sanctity into it. The inability of the people, who had done so well in bringing together and constructing all of the different elements of the Mishkan, to actually finally erect it, tells us, on the one hand, how difficult the task of making a holy place in the world is. You can get all the various components together, but actually making it happen is beyond the efforts of the community, even when working well together. On the other hand, it seems that this is the case only because God wanted to help Moshe out. Moshe was upset at being left out of the work on the Mishkan, and that seems to be why God made the beams too heavy for anyone to lift, leaving this final job to him, the leader of the nation. It would seem that this is what really lies behind the failure of the people to raise up the Mishkan, not some basic, deeper difficulty.

However, I think that the idea that Moshe, after overseeing the entire process, bringing the instructions from God to the Jewish people, and managing them as they proceeded to bring it all together, did no work seems preposterous. Can it honestly be said that Moshe did not do any work on the Mishkan? Being an executive, a manager, is not called work? Well, apparently not. Apparently, if one is not so committed to the task that he or she wants to actually be involved in it directly, to get their hands dirty, they are not really working on it. In a world where an educator is a success when he has risen to a position where he actually doesn't teach anyone anything, but just manges those who do, this insight is downright revolutionary. In a world where those who actually do the work are at the bottom of the totem pole, and those who have been lucky enough or aggressive enough to manage those people typically take obscenely large salaries for ultimately doing nothing, this is a revelation. Real leadership is about being part of the team that really does the work. Real leadership is about so badly wanting the job to get done well that you just have to get directly involved, you have to get your hands dirty, and not about profiting from the work of others. God understood that this is what Moshe's leadership was all about, and therefore left the ultimate job of raising the Mishkan to him.

Now for the most interesting and challenging part. The stage is set, Moshe will be given the chance to demonstrate the true extent of his leadership by taking on the hardest job himself, by finishing the task, and then he fails! He can't do it! It is too heavy for him as well! And what is God's solution: 'move your hands around as if you are doing something and it will look like you are getting the job done'. And, unbelievably, it works! The Mishkan rises up on its own accord! What can this possibly mean? What can the purpose of this charade be?

Moshe fails to raise the beams of the Mishkan because, as we said earlier, the really big tasks, the impossible job of making the world a holy place, a place with God in it, are, in fact, too big for any collective, no matter how dedicated, talented, and hard-working, or for any individual, no matter how gifted, to accomplish. They are the ongoing challenges of being in this world, they are the tasks which we never complete. Our job, as leaders - and when it comes to making a place for the divine in this world we are all leaders - is to make the effort even though we know we will ultimately fail, to inspire others to make the same effort, and to have faith that the energy generated by these efforts, and the example they set, will, indeed, make the Tabernacle 'rise up by itself'. Our job is to be a model for others, to move our hands as if we are actually accomplishing something, knowing, on the one hand, that the task is too big for us and, on the other, that it will get done.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Pekudei Divrei Torah from previous years