Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

One way to look at some of the internal conflicts currently engaging the Jewish people is to think about the issue of flexibility. A large group of Jews, usually identified as Charedi or ultra-Orthodox, along with some who are not exactly Charedi but share many of their views, advocate a Judaism which they charachterise as unchanging, ancient, authentic, and unbending. One hears from this camp statements such as "the Torah is eternal, does not change, and will not change", or, "we live the way that Jews have lived for thousands of years, untainted by things like progress or modernity, and we will continue to do so, rejecting the values of the outside, non-Jewish world". Although it is obvious that the Rabbis of the Mishna and Talmud did not speak Yiddish, were not followers of this or that Chassidic Rebbe, and did engage quite profoundly with the Greco-Roman culture around them (the word Sanhedrin, the name for Judaism's highest legislative/judicial body, is from the Greek), the Charedim still make the claim that, somehow, Judaism has never changed, and they are the people who have not changed along with it. An unbending, inflexible loyalty to this supposedly immutable tradition is their hallmark.

At the other end of the spectrum stands a mix of modern Jewish movements, including the Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, and secular communities. For them, in varying ways, embracing and accomodating modernity is a central value of their Jewish world view. Their religious life, though certainly containing varying measures of traditional belief, practice, and ritual, is ultimately all about change, accomodation, and a rejection of what is perceived as outdated or irrelevant in favor of a way of being Jewish that is, first and foremost, fully in synch with living in a modern, open, western, culture.

In the middle you have me - make that us - the modern Orthodox who, in a range of different ways, attempt to navigate between the competing values of openness to the world and it culture on the one hand, and a commitment to traditional Jewish life and law (which, we believe, promotes that very openness) on the other. Modern Orthodoxy must be flexible, able, in one paragraph, or one sentence, to express being in many worlds at once; the world of the Bible and Talmud and the world of Shakespere; the world of Maimonides and the other great codifiers and philosophers and the world of the Beatles and Barak Obama (or Mitt Romney); the world of halacha (traditional Jewish law) and the world of Kant and Kierkegard. To be modern Orthodox is to embrace a flexibility which, we believe, has always been the hallmark of Torah-true Judaism, the way that Jews always saw the world, and the reason they were able to survive and thrive.

Purim, I believe, gives us an excellent lesson in what this flexibility is and how it works. Set in the Persian Diaspora, never mentioning the name of God, Esther is the book, and Purim the holiday, which are about the way we are today: having to navigate our paths in a non-Jewish world (and this is just as true in Israel, in its way, as it is in the Diaspora, in its), trying to live as Jews in a very rich, but often threatening and tempting, non-Jewish culture.

Let's start with the easy part: Purim's negative take on inflexibility. Achashverosh's kingdom is ridiculously unbending. The crux of the Purim story, the reason the Jews had to fight their would-be murderers and kill over 75,000 of them, is the weird fact that once Achashverosh had listened to Haman, and decreed that the Jews were all to be killed on the 13th of Adar, there was nothing he, or anyone else, could do about it - "the writing which is already written in the king's name, and sealed with the king's seal, cannot be revoked." Rather than just changing his mind and calling it a day, Achashverosh allows Esther to write a counter-decree, giving the Jews the right to kill their enemies, which leads to the good-for-the-Jews but quite-bloody-for-the-Persians result. From Achashverosh's perspective, a more damaging indictment of inflexibility that 75,000 dead people is hard to imagine.

In addition to the non-revokable decree business, the hierarchical nature of Persian life, as depicted in the Megillah, with its many different types of officers, advisors, servants, and functionaries, points to a highly-structured society, one in which even the relative status of husbands and wives in their homes is subject to silly royal decree (chapter 1, 20-22). Another royal rule, forbidding, upon pain of death, anyone from enering the king's court without being invited, is dramatically broken by Esther when she comes, unbidden, to plead the cause of the Jewish people.

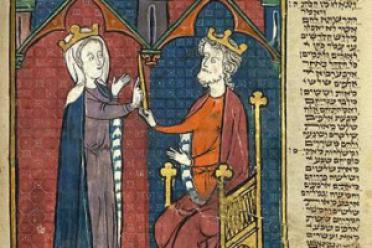

As opposed to the highly structured, unbending nature of Perisian life, where even drinking parties had their rules and regulations, the behavior of the heroes, Esther and Mordechai, is all about being flexible. The halachic problems surrounding Esther marrying Achashverosh are profound, both because he was a non-Jew and, more problematically, because Esther may have already been married to Mordechai. The Megillah, and, in its wake, Jewish legal discussion, demonstrate a remarkable ability to creatively navigate this problem, and find ways to explain and even excuse the behavior of Esther and Mordechai. In addition, the ease with which Mordechai navigates the Royal Court, and the high position he attains, also indicate a highly developed ability to live as a Jew while fully engaging in a foreign, and often problematic, culture. Of course, when push comes to shove, Mordechai remains true to his Jewish values, refusing to bow to Haman, but he, and Esther, never stop navigating their way through both cultures and both value systems, doing their best to know when to be more Persian, when to be fully Jewish. As their Persian names would indicate, they were fully of both cultures, for better and for worse, which is exactly the reality we all need to recognize and deal with, if our lives, and our Judaism, are to be real, authentic, and healthy.

A central message of the Megila, ונהפוך הוא - "it was turned upside down" - indicates that it is not just the content of Haman's decree, but the very order of this inflexible and highly structured society, which needed to be overturned. The riotous and antinomian way in which Purim is celebrated, (indeed, the very fact that the Rabbis could declare a new, post-Biblical holiday), getting drunk until we "can't distinguish between cursed is Haman and blessed is Mordechai", the cross-dressing, all indicate that it is unbending, inflexible structure that is our true enemy on Purim, and that the values it teaches us are flexibility, and an openness to innovation and change.

In one of the climactic moments of the Megillah, when Mordechai is trying to convince Esther to risk her life and plead the Jewish case to the king, he says "who knows if, perhaps, it was for a time such as this that you came to royalty" (chapter 4, 14). His openness to the possibility that this is her destiny, though unsure that it is, unsure that her living as the secret Jewish wife of Achashverosh is a good thing, an irrelevant thing, or perhaps a sin, is precisely the kind of honest lack of certainty that is called for when trying, as a Jew, to live a real life. We try to find the right path, do the right thing, and balance correctly the various elements of our lives, but we are far from certain about the rightness of any given direction. In fact, at the end of the Megillah, we are warned that one can go too far, and become too closely connected to non-Jewish society. We are told that Mordechai, now viceroy of Persia, was "acceptable in the eyes of many of his brethren". The Rabbis tell us that this means acceptable to many, but not all; some saw him as having strayed too far from Jewish tradition, and gotten too close to the Royal Court, the center of Persian culture.

Purim, then, lays it all out for us. We all live within the empire, whether it's America today (no matter where on earth you live) or Persia then. God is not immediately, obviously, present in our lives; we are, largely, on our own, armed only with our Jewish traditions, and expected to function within our contemporary cultural reality. We will have to whether we like it or not, as any attempt to withdraw from the influences of the reigning, dominant culture, short of retreating, Essene-like, to some desert hideaway, is just a charade, that's how powerful the influences of culture, language, technology, and media are, even in Boro Park or Benai Brak. Judaism wants us, like Esther and Mordechai - though, hopefully, in happier circumstances - to exhibit the flexibility to know and accept that we must live in the world, and live as Jews. Doing those two things is actually what being Jewish is all about, and it has been ever since Abraham, Sarah, and our other forebears had to deal with Egypt, various Canaanite nations, and whatever else was happening in their world. The inflexibility advocated by some, the game of make-believe in which we pretend to cut ourselves off from the world in which we live, was never the normative Jewish approach, and must be overturned, as Esther and Mordechai overturned the silly and ultimately ruinous inflexibility of Achashverosh's Persia.

Purim Sameach,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Purim Divrei Torah from previous years