Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

Over the past 200 years or so, the Jewish people have struggled with the question of how to relate to the new, more liberal denominations and movements which began to take shape with the advent of emancipation and enlightenment. How should communities who see themselves as bearers of the Jewish tradition react to communities who fly the banner of reform, change, reassessment, and, at times, even rebellion? In the main, the more traditional approaches were, and remain, very negative in their attitudes towards these new approaches to Judaism, while some traditional Jews do call for a greater degree of openness and respect for them. In this week's parha, שלח - Shlach - there is a remarkable piece by the Ramban (1194-1270), which I think may point to an interesting and productive approach to this issue.

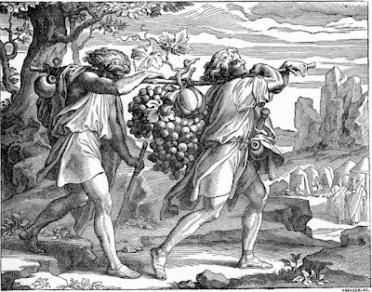

The bulk of Shlach is given over to the sad story of the מרגלים - the spies sent by Moshe to check out the situation in the Land of Canaan in anticipation of entering and taking the land. The spies come back and essentially recommend abandoning the mission: "...the nation that dwells in the land is strong, the cities are fortified, and very great...the land which we went to see is a land that devours its inhabitants, and all the people we saw in it were men of great stature...we seemed in our own eyes to be like grasshoppers, and that is how we seemed in their eyes." The negative assessment has its effect, and the people clamor to return to Egypt, rather than face the terrors of trying to conquer Canaan. God, of course, is very upset. He conderns this generation as faithless cowards, and promises that they will get just what they want: they will not enter the land. Instead, over the next forty years they will die in the desert, and it will be the next generation which will enter the land.

Immediately after this tragic story, there is a series of laws pertaining to sacrifices in the Temple. The series begins with the phrase: "And God spoke to Moshe, saying: Speak to the children of Israel and tell them that when they enter the land they will dwell in, which I am giving to them..." and goes on to teach us a law about adding a grain offering and libation of wine to various animal sacrifices which will be brought to the Temple. After that, with the same preface, "...when you enter the land which I am bringing you to...", we have the laws of giving חלה - challah - a portion of the dough used to make bread, to the priests. Why these laws are written here now is a matter of some discussion. Some say that these laws, relevant to the Temple in Jerusalem, and introduced by the phrase "when they enter the land", are here to reassure the people that their children will, in spite of the sin of the spies, ultimately get to the land of Israel, build a Temple, and offer sacrifices.

After these two sections, we have the following: וכי תשגו ולא תעשו את כל המצות האלה אשר דבר ה' אל משה - "And if you err, and do not do all these commandments which God spoke to Moshe...". The section goes on to mandate a sin offerring, for the entire congregation or for an individual, who mistakenly sinned by not doing "all that God commanded you through Moshe, from the day that God first commanded and on, through your generations." If however, this is done on purpose, the punishment is כרת - being eternally cut off from the Jewish people (we'll leave the discussion of what כרת is exactly for another time).

The commentators have a real problem understanding exactly which accidental crimes these sin offerrings are meant to atone for. Nachmanides (the Ramban) begins his explanation by saying "The meaning of this section is hidden." The problem seems to be the sweeping, far-reaching language used to describe the accidental sin the sacrifice atones for: "all these commandments...all that God commanded Moshe." At first glance, this seems to be referring to someone, or a whole community, who break ALL the laws of the Torah accidently, which is difficult to imagine. For ths reason, many of the commentaries go along with the notion found in the halachic Midrash, the Sifri, which says that this is talking about an accidental worshiping of idols. The verses refer to someone, or a group who, by mistake, are gulty of עבודה זרה - idolatry. Realizing their mistake, they then bring this sacrifice.

Nachmanides goes along with this to a degree, and accepts that idolatry would include a breaking of all the commandments, and is a good example of the behavior we are talking about, which, if done accidently, neccessitates a sacrifice, and, if done on purpose, is punished by being "cut off" - כרת. However, he points out that this is not what the Torah says. The simple reading of the verse more obviously refers to an accidental breaking of all of God's laws, every one of them, not just idol worship, as bad as that may be. He therefore arrives at a different understanding of the verses. He insists that "...if you will not do anything that He commands you..." means what it says, and explains: "For instance, he who goes and joins one of the other nations, to behave like them, and does not want to be with the congregation of Israel at all, by mistake, as can occur with an individual child who was taken captive among the nations. Or a congregation which, for example, thinks that the time of the Torah has already passed and it was not given for all the generations... or if they forget the Torah. And this has already happened to us due to our sins, as in the days of the wicked kings of Israel, like Yeravam, when most of the nation totally forgot Torah and Mitzvot, and as is described in the Book of Ezra during the Second Temple [when the returnees from the Babylonian Exile had forgotten most or all of the Torah's laws], and that is the meaning of the language here, that this accidental sinning mentioned here is referring to all of Torah and Mitzvot."

What is remarkable about this Ramban is that he identifies a congregation or individual who honestly believe that the Torah has become irrelevant, or who have been led to reject the Torah due to bad leadership or historical circumstance, as making a mistake, one which, once they realize what they have done, can be atoned for with a sin-offering. I believe I am not wrong in saying that this is revolutionary, and that most traditional Jews today would say that someone thinking the Torah is no longer binding, or relevant, is simply a heretic, and should not be given the benefit of the doubt conferred by the Ramban's calling this a "mistake".

It would seem that, according to the Ramban, to be a heretic or willful non-believer, one needs some degree of rebelliousness, some sort of knowing that what he is doing is NOT what Jewish tradition wants, not what God, history, the Torah, and the Jewish people expect of him or her, but what the heck, let's do it anyway. This kind of individual or group is known to us in Rabbinic literature as one who "knows his Creator, or Creator's will, and willfully rebels against it". I would argue that this kind of person is pretty hard to find. The great majority of reforming or liberalizing movements saw themselves, and certainly still see themselves, as following the dictates of history, of their legitimate religious leadership, of an evolving Jewish reality. They do not, I think, see themselves as willful rebels against God and His Torah.

As if this was not far-reaching enough, the Ramban goes on to say more. He explains why these laws pertaining to the sin-offering brought for mistakenly not keeping the entire Torah are located here, just a few verses after the sin of the spies. He says that the Jews had just rebelled against God, saying that they wanted to return to Egypt, to once again be in the same situation they had been in before the Exodus: without Torah and without Mitzvot. This section about the sin-offering is here to tell them, and us, that even for the worst sins, even for idol worship, if done mistakenly, there is atonement. It is only those, like the generation of the spies, who behave in a high-handed, rebellious manner, who will be denied atonement and cut off. Again, the Ramban seems to be extending an olive branch of understanding to those who seem to be rejecting the Torah, and God's will in general, by reminding them that if they mean well, and their rebellion is actually just an honest mistake, they will not be cut off, but can be forgiven. This doesn't help the generation of the spies, who were given every opportunity to listen to Moshe, Aharon, God, the two good spies, and behave correctly but rejected them, but it does reassure us that it was precisely their stubborn rebelliousness that is being punished; they are the exception, not the rule.

This remarkable position demands of us a whole different way of looking at non-traditional approaches to Judaism (or at traditional Judaism if you are on the other side of the fence). While perhaps not as liberal as a fully pluralistic view, which would accept and respect approaches we might strongly disagree with, Nachmanides certainly takes the sting out of thinking that a new movement or direction is wrong. We may think that they are wrong, but the liberalizing, modernizing tendency they represent ("the time of the Torah is past") is seen by the Ramban as more of a mistaken belief than a rebellion. There is very little room for anger here, very little reason to be too negative with those whose approach to Judaism seems wrong to us. At worst, they are making a mistake, an error in judgement. We might, like the Ramban, hope that they come to their senses and realize their error, but we would be wrong to attack them too severely.

I also detect in the Ramban an openness to a freedom of thought that I think we would do well to adopt. The way he describes the forgetting or abandoning of Torah and Mitzvot as a mistake indicates that he undertands that in matters of belief there is room for honest error; not everyone we diagree with is bad, wicked, or willfully wrong-headed, they just see it differently than we do. This is a giant step towards an openness to other opinions and approaches, a willingness to accept that others, with whom we may disagree, are acting in good faith. A further positive step, building from the Ramban and moving forward, would be to say that while we may disagree with those who see things differently from us, we are all just trying to understand what God's hand in history wants us to do as Jews, and those who come to decisions different from ours are not neccessarily wrong, they just have come to different conclusions, which we can respect and even learn from.

Even without this added step to greater acceptance of positions we do not share, the Ramban's willingness to call people who have abandonded Torah and Mitzvot completely "mistaken", is a tremendously decent, open, and humane step forward, in that it respects the good intentions and integrity of even those whom we belive to be very wrong.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Shlach Divrei Torah from previous years