Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

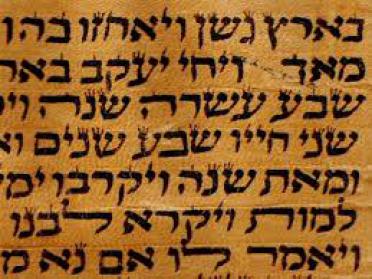

The parsha of Vayechi is unique in that it follows the previous parsha, Vayigash, with no physical break on the page of the Torah. All the other portions of the Torah have a kind of page break, like a new paragraph, between them. Vayechi is the only one that picks up immediately after the parsha before it, with the last word of Vayigash followed immediately, with no physical gap at all, by the first word of Vayechi.

The Rabbis, of course commented on this, and tell us the following: In Vayechi Yaakov passes away, and is buried in Canaan, leaving his children and grandchildren, the Jewish people, in Egypt. The absence of a gap between this and the previous parsha, a phenomenon which in Hebrew is called סתומה – setumah, blocked, without any space - echoes the new situation the Israelites will find themselves in after Yaakov’s demise: just as the parsha is “blocked”, so, too, their hearts and eyes will be blocked, closed, by his passing, which ushers in the beginning of their oppression in Egypt.

Now, this sounds like a kind of pun or word play. The parsha is called “setumah”, so the Jews are in that state as well. They are “stumim”, blocked, closed off, following the central event of the portion, the death of Yaakov.

First, we must ask what this being blocked off means, exactly. In addition, we need to ask how the Israelite’s oppression began at this time; there is no hint of that until later in the Biblical narrative. How is Yaakov’s death connected to this mysterious blocking, and the beginning of oppression? I would also ask about this strange way of communicating this message of being “blocked” or “closed” to us. Is the "setumah" connection simply a visual and linguistic signal? Why is this the way the Torah informs us of the closing of the Israelite’s hearts and minds?

I’d therefore like to look a bit more closely at what it means for there to be no blank space between the last parsha and this one. What is the significance – beyond the “setumah”- “setumah” pun – to the absence of blank space in the Torah scroll?

The Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, known as Nachmanides, who lived in Spain and Israel, 1194-1270), in his preface to his commentary on the Torah, basing himself on passages in the Talmud, discusses a primordial Torah, which predates the creation of the world, and which was written in black fire on white fire. This would mean that this divine Torah consisted of both the letters – the “black fire” - and the scroll itself – the “white fire”. This gives the spaces between the letters, the empty parts of a Torah scroll, a primordial sanctity as well. This idea is picked up later by the Hassidic master Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev, who says that, in the future, we will be able to read the spaces in between the letters as if they were letters themselves, giving us access to new, hitherto unknown Torah. If this is the case, if the empty spaces in the Torah are somehow an integral part of the Torah – though somehow hidden – then the absence of space, as is the case of the setumah situation at the beginning of the parsha, is the absence of something important, symbolized by the white fire.

But what is the importance, the sanctity, of the blank spaces between the letters and parshas of the Torah? Well, in a regular book, which, of course also has blank spaces dividing letters, words, paragraphs, and chapters, these serve as background, setting, the place on which the actual story takes place. Large page breaks indicate a change of setting – emotionally, chronologically, or geographically – and small breaks, in between paragraphs, for instance, indicate a smaller shift of focus or emphasis. This, on a simple level, is obviously how the blank spaces in a Torah scroll function. But the sanctity of these white spaces, their “white fire”-ness, teach us something about background, setting, and space. It teaches us that there is sanctity to that as well. The setting of our lives is also an arena where holiness, and content, and meaning, can be achieved, or lost.

The Israelites who had recently come down to Egypt were living in a totally new, and very foreign, setting. The scene, the background, of their daily lives had drastically changed. They were now strangers in a strange and often threatening landscape. The only real connection they had with their former setting – their identity as Israelites – was their father and grandfather, Yaakov. He, as the elder of the family, represented the past, the roots, and the foundations, of who these people were. He was the holy, sacred, white fire, on which the black fire of the details of their actual day to day life in Egypt could be played out, the Jewish background and foundation to a very un-Jewish reality.

With the death of Yaakov, that white fire was lost. The Israelites no longer had with them the living presence of Avraham and Yitzchak, embodied by a Yaakov who had grown up in their home. The basic facts of their history and identity, the covenant between God and Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov, and the relationship to the land of Israel, from which their worldview was meant to flow, were now just disembodied memories. Now, they were really and truly in Egypt, which may be what is meant by saying that, with Yaakov’s death, the oppression begins. Not, apparently, a literal, physical subjugation by the Egyptians, but, rather, the alienation and disassociation which comes with being rootless and disconnected in a strange place. They had lost a way of being in the world, of properly and naturally seeing and feeling.

In Egypt, with his children and grandchildren, Yaakov’s role was to be the living link to where they were from and where they really belonged, the link to who they really were. His death, and subsequent burial back in Canaan – a final abandonment of his children to the reality of Egypt - is precisely the loss of what a father or mother can and must give their children: a basic sense of where they come from and who they really are; with what set of values and assumptions, with what legacy, they are meant to see the world and act in it. It is within that setting - situated within the white fire, the holy background, which our parents supply us with - that we can go on to successfully write the stories of our lives – the black fire.

The lack of space between last week’s parsha, Vayigash, and this week’s parsha, Vayechi, making Vayechi a parsha setumah, echoes and illustrates what it is to be lost in Egypt, cut off from your cultural, religious, and familial roots. With the death of Yaakov, the Israelites will now be without the support of their father and grandfather, their link to the place, ideas, and commitments that make up their culture, identity, and destiny. They will be setumim – with eyes no longer able to really see, and hearts no longer able to fully feel - adrift in a foreign culture and reality, rootless, without a tangible, knowable past. That is the real beginning of exile.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Vayechi Divrei Torah from previous years