Every week, parshaoftheweek.com brings you a rich selection of material on parshat hashavua, the weekly portion traditionally read in synagogues all over the world. Using both classic and contemporary material, we take a look at these portions in a fresh way, relating them to both ancient Jewish concerns as well as cutting-edge modern issues and topics. We also bring you material on the Jewish holidays, as well as insights into life cycle rituals and events...

I have always been bothered by the approach taken by Rashi on the verses at the start of Parshat Va'yigash. In last week's parsha, Miketz, Yosef seized his younger brother Binyamin, on the pretext of punishing him for having stolen Yosef's goblet (Yosef had actually framed him, by planting the goblet on him as a pretext to arrest him and keep him in Egypt). Yosef has told his other brothers to go back home, to Canaan. It would seem that Yosef wanted to remain in Egypt with Binyamin, and seperate pemanently from the rest of his brothers who, after all, had planned to sell him into slavery. Yehudah, however, has sworn to Yaakov that he would take responsibility for Binyamin, and bring him back home to Canaan, which is what he attempts to do at the start of our parsha.

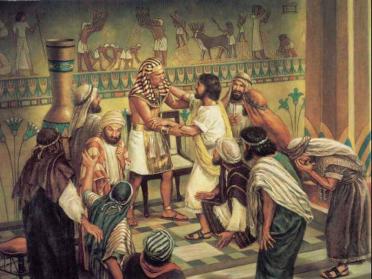

He approaches Yosef, and in a long, heartfelt speech, explains that the loss of Binyamin will certainly mean the death of Yaakov, for whom this final blow, after the loss, years before, of his beloved Yosef, will be too much. He expains that he has taken responsibility for Binyamin's welfare, and offers, dramatically, to remain in Egypt in his place.

What is strange about Rashi is the way he interperets these very moving verses, in which Yehudah seems to really speak frankly and openly, and take full responsibility for the situation. Rashi sees an undercurrent of threat in Yehudah's apparently respectful and beseeching words to Yosef. When he says "please don't be angry with your servant" [meaning himself, Yehudah], Rashi says this indicates that he spoke harshly to Yosef, in a way that would be expected to arouse his anger. When he then says "for you are like Pharaoh" - which seems like a compliment and admission of Yosef's power, Rashi says that he was actually berating and threatening him for taking Binyamin - "you will suffer from leprosy as an earlier Pharaoh did for taking my grandmother Sarah...just as Pharaoh promises and does not deliver, so do you, is this the way you keep your earlier promise to keep an eye on Binyamin? And, if you anger me I will kill you as well as your master, Pharaoh." Why does Rashi see this undercurrent of aggression and threat in a speech which appears to be, and is meant to be, all about contrition and supplication?

Perhaps Rashi is bothered by the thought of Yehuda being completely subservient to Yosef, who has actually dealt very badly with the brothers, first accusing them of being spies - something, the Ramban points out, he did not do to any of the many other foreigners who came to Egypt for food during the years of famine - then demanding that they bring their yongest brother, Binyamin, down to Egypt, and, finally, planting his goblet on Binyamin to entrap him and falsely accuse him of theft. The Ramban tells us that Yehudah suspected that this was the truth, and knew that Yosef had not dealt fairly with him and his brothers.

Yosef's power, and the promise which Yehudah had made to Yaakov to be responsible for Binyamin, as well as his guilty concience about the way he and his brothers had treated Yosef years before, forced him to be contrite with Yosef, to beg him to free Binyamin. However, this does not mean, Rashi tells us, that he has lost sight of the true moral and ethical dynamic at work here. Yosef has not been honest or reasonable with the brothers, he was wrong to take Binyamin, and the undercurrent of aggression which Rashi finds in Yehudah's words is meant to express that.

It would seem that Rashi believes Yehudah was caught between the need to curry favor with Yosef, for Binyamin's sake, and the desire to keep a grip on the truth. Rashi therefore interprets Yehudah's words as double-edged, so as to give him the chance to retain the moral high ground: he has to speak contritely to Yosef, but it would be wrong for him to not, in some way, also communicate the truth to him about his unacceptable behavior.

Next week, in Parshat Va'yechi, Yaakov will bless Yehudah and tell him that "the scepter shall not be removed from Yehudah" - meaning his descendants, the dynasty of King David, will rule Israel. Yehudah's behavior here, his taking responsibility for his younger brother's welfare, is seen as a crucial indicator of his aristocratic personality, his ability and right to lead. It may be that Rashi, in the double-edged way he understands Yehudah's speech to Yosef, is telling us that leadership is precisely about bridging the gap between the practical needs of the state - in this case, saving Binyamin - and keeping a grip, if only a semantic one, on what is right and wrong. His insistence that Yehudah was not completely subservient to Yosef, and actually, at least by implication, called him on his unethical behavior towards the brothers, and, ultimately, their father Yaakov, is an interesting demand on our leaders to not allow the needs of realpolitik to ever let us forget our moral compass.

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Shimon Felix

Get inspired by Vayigash Divrei Torah from previous years